LDMS Students Asked To Ponder Question In Project

In a quiet classroom at Lylburn Downing Middle School, students watched attentively as history teacher Eric Wilson flipped through presentation slides of old photographs —black-and-white faces from yearbook pages and graduation composites. One image showed the first Black graduating class from 1944. Another, a football team from the same year, proudly posed in their uniforms.

But Wilson wasn’t just showing students the past. He was asking them a question that turned their focus to the present and future: What will you leave behind?

As part of a multi-day history project held in conjunction with Black History Month, Wilson led presentations for all LDMS students in grades six through eight, exploring the nearly 100-year story of their school and inviting them to consider their own place in its continuing legacy.

“It’s a history lesson, sure,” Wilson said later in an interview, “but it’s also kind of a civics lesson. It’s about being mindful of who’s around you now — and what you’re helping to pass on.”

The centerpiece of each class session was a 30-minute slideshow tracing the school’s evolution, beginning with the 1865 Randolph Street Freedmen’s School and culminating in the present-day LDMS.

Along the way, students learned about Lylburn Downing School’s origins as a segregated school for Black students in 1927, its expansion into a full high school, the desegregation of local schools in 1965, and the eventual consolidation of high schools into Rockbridge County High School in the early 1990s.

Throughout the presentations, Wilson emphasized that history isn’t just something that happens in textbooks. It happens in hallways and classrooms, in cheer routines and school songs, and even in the everyday methods students use to get to school.

“Every generation leaves something behind,” he told students. “Some of it ends up behind glass in a trophy case. Some of it lives in memory. But either way, the question is: What story will your time here tell?”

To bring those stories to life, Wilson invited a slate of guest speakers spanning decades of LDMS history.

Former student Stanley Land joined eighth-graders via Zoom to share memories of attending the school before integration. Vice Mayor Marylin Alexander, who experienced desegregation as a student in the 1960s, recorded a video message reflecting on both the challenges and pride of her era. Lexington Mayor Frank Friedman, LDMS Latin teacher Laura Joyner, and former teacher Amanda Conway also shared their experiences as part of the school’s evolving story.

Their testimonies added emotional weight to the timeline. Alexander spoke of how, in her youth, parents in the Black community pooled their own money to fund an extra teacher — so students wouldn’t have to leave home just to finish high school. Others reflected on what it meant to be a Trojan in decades marked by change and perseverance.

“These are people whose stories help students see that they’re not just walking through a building,” Wilson said. “They’re part of something much larger.”

The idea of legacy became even more personal during the project’s culminating activity: a writing prompt titled “What do you want to see in your school trophy case?”

Students were asked to think broadly — about awards and achievements, but also about values, moments, and memories that deserve to be honored. Responses were submitted online and archived, with the goal of shaping future additions to the school’s display areas.

“It’s a good entry point,” Wilson said of the displays. “A trophy case is something students see every day, so we used it as a metaphor. What kind of recognition matters? What do we choose to remember? What deserves to be preserved?”

Wilson hopes that the project will lead not only to reflection but also to action — perhaps even the expansion of the school’s trophy cases or new displays in the Downing Alumni Heritage Room, housed in the adjacent community center.

He also sees deeper possibilities. “I’d love to see something non-material in those displays — something valuebased,” he said. “A mural, a statement, a piece of writing that speaks to who this generation is. Something that isn’t just a piece of plastic, but a story worth telling.”

The latest version of the initiative builds on a similar effort in 2023, when the school held an assembly that brought together students, alumni, cheerleaders, and musicians to celebrate the school’s roots through performance and storytelling. This year’s approach, Wilson said, offered a quieter but equally powerful way to connect.

And while it may not become an annual tradition, he sees potential for repeating the cycle every few years — especially as Lylburn Downing approaches its centennial in 2027.

“Legacy isn’t just something old,” Wilson said. “It’s something we make every day. You stand on someone else’s shoulders — and you make space for someone else to stand on yours.”

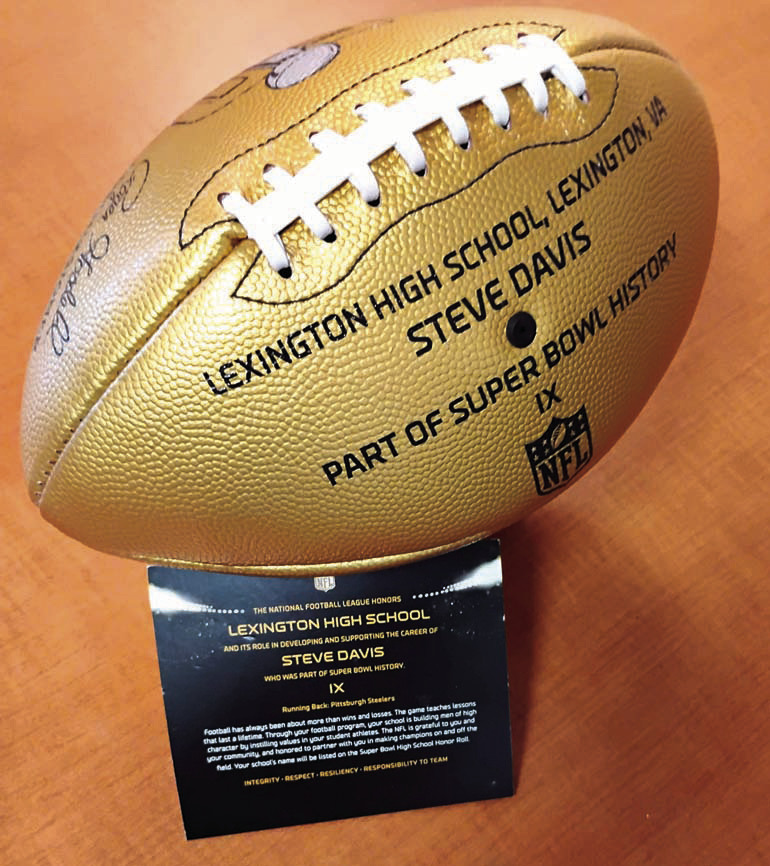

ABOVE, Stanley Land, a former student of Lylburn Downing School before desegregation, speaks with eighth-grade students via Zoom as part of a classroom presentation on the school’s history. Teacher Eric Wilson, who organized the project, looks on from the back of the room. AT RIGHT, a gold football awarded to Downing alumnus Steve Davis, who played in Super Bowl IX, was shown to students as an example of how both athletic achievement and local legacy could be honored in a school display case. (photos courtesy of Eric Wilson)

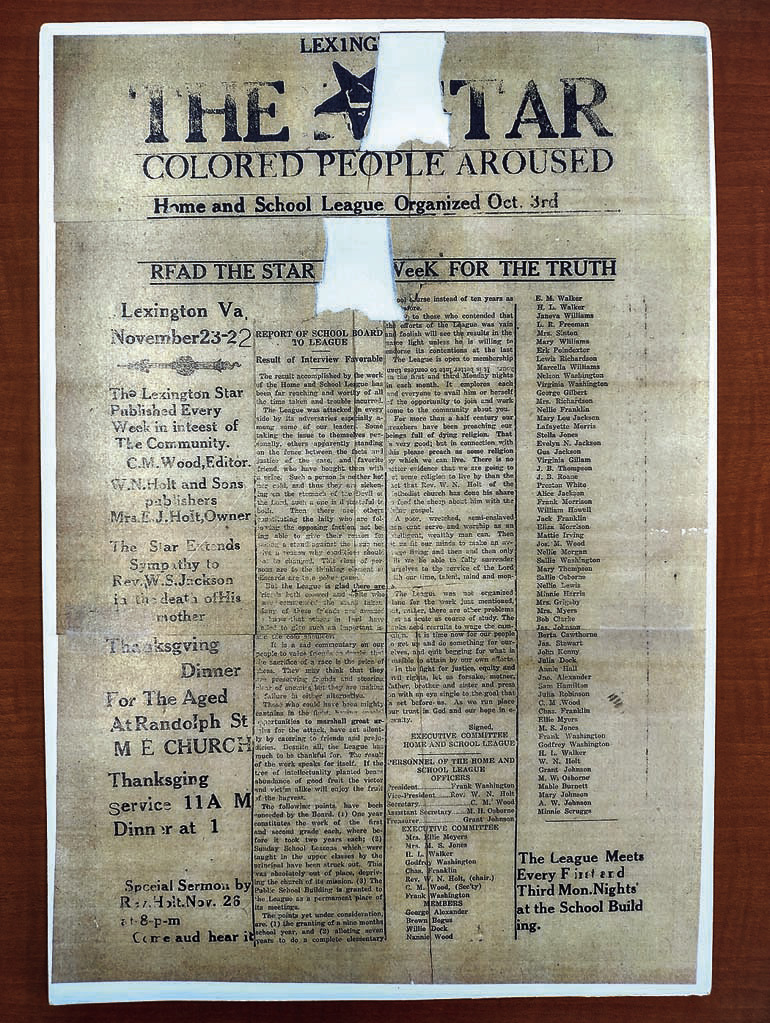

AN EDITION of The Lexington Star features the headline “Colored People Aroused – Home and School League Organized Oct. 3rd,” documenting community efforts that helped lay the foundation for what would become Lylburn Downing School in 1927. (photo courtesy of Eric Wilson)