August 1974 — Lexington loves Mel Greenburg.

All summer, people have hardly been able to talk about anything other than the ride he took the whole town for. And not even the victims of his little con game are mad at him. Everybody says it was just like “The Sting.”

It all began right after graduation, when Mel swooped into town in a sleek Matador sedan with California license plates and set up headquarters at the Keydet-General motel. News travels fast in a small town, so even before Mel put his ad in the Lexington News-Gazette, people were asking each other: “You trying out for the big movie? There’s a Hollywood producer here, you know.”

And try out they did — housewives stood in line outside Mel’s room together with queens of local society, students with professors, farmers and merchants, even one local preacher. And Mel hired just about everybody — mostly as bit players. As they’d leave his “interview room,” they’d all comment how thorough and professional he seemed.

He told them the movie was going to be called “The Southern Pass,” and that it would be about the Civil War — Stonewall Jackson, actually, who taught at Virginia Military Institute and married the Washington College president’s daughter. It was going to be a comedy, he said — a musical comedy. With a nude scene.

Lexington has always operated on trust, and everybody fell for it — at first.

And why not? Mel promised to pay $22 an hour for extras, just for showing up on the set, with bonuses while the cameras were rolling; $500 for actors with speaking roles; a staggering $12,000 for the lady who’d star in the sex scene.

The setup did have class. Mel looked the part from his clothes to the flashy car. His business card had a Sunset Boulevard address.

He worked with detached coolness, even while inspecting the undraped forms of the dozen or so women who tried out for the nude scene. He was, in short, very much like one of the Hollywood producers you see in movies about Hollywood producers.

But it couldn’t last forever. Before long, a few people began to be suspicious. Mel was becoming more extravagant with his promises with each hour, and now he was saying he’d booked Audrey Hepburn, Burt Lancaster, Phil Silvers and Kirk Douglas for “Southern Pass.” On reflection, the pay scales seemed awfully high. And the California car was impressive, but what Hollywood film czar would drive across the country rather than fly?

So the investigations began. And in hardly any time at all, Mel’s scheme crumbled. Two Washington and Lee journalism professors telephoned Frank McCarthy’s office in Hollywood. (McCarthy, a VMI alumnus, produced “Patton” — he really did.) McCarthy’s people told them that nobody in Tinseltown had ever heard of Mel Greenberg. A check with the California Motor Vehicles Bureau showed Greenberg’s car was registered to a defunct mas¬sage parlor in Pasadena called the Tiki-Tiki Club. The address on Mel’s business cards proved to be a parking lot. And screen agents for Hepburn, Lancaster, Silvers and Douglas guffawed at the idea that their clients had signed for a musical sex comedy about Stonewall Jackson. (One result of all the calls everybody was making to California was that the local telephone operators became the first to know something was up.)

Mel skipped town, of course. But before long he was caught in Hillsborough, Ohio, where — naturally — he was setting up a similar scheme. People in Hillsborough must be more cynical than we are in Lexington, though, because they called the law the minute Mel announced he was a talent scout for a Rock Hudson movie.

As it turned out, Mel’s only technical crimes in Lexington were cashing a couple of bad checks at the Keydet-General and failing to pay his motel bill. And Norman Anderson, owner of the motel, wasn’t too upset, because he made more than he lost as a result of the crowds who stopped in at the motel restaurant while waiting for their auditions.

Mel was in jail in Hillsborough until mid-August, fighting extradition back to Lexington. He said he didn’t expect he could receive a fair trial in Lexington, that the people in the little college town were filled with “hostility” and “resentment.”

Little did he know. On the contrary. “We ought to pay him for the entertainment he’s provided,” commented one man. “How can you hate the guy?” asked a woman in a letter to The News-Gazette. One young man told Newsweek (which, like much of the national media, reveled in the story): “We’d never seen a real con man before, and we feel proud to have been in on this one!”

“Free Mel Greenberg!” bumper stickers began appearing. So did T-shirts exhorting “Come Back Mel — I’ll Make Your Movie.” There was talk of proclaiming a “Mel Greenberg Day” when he came back to town, and stringing a banner across Main Street in front of the County Courthouse.

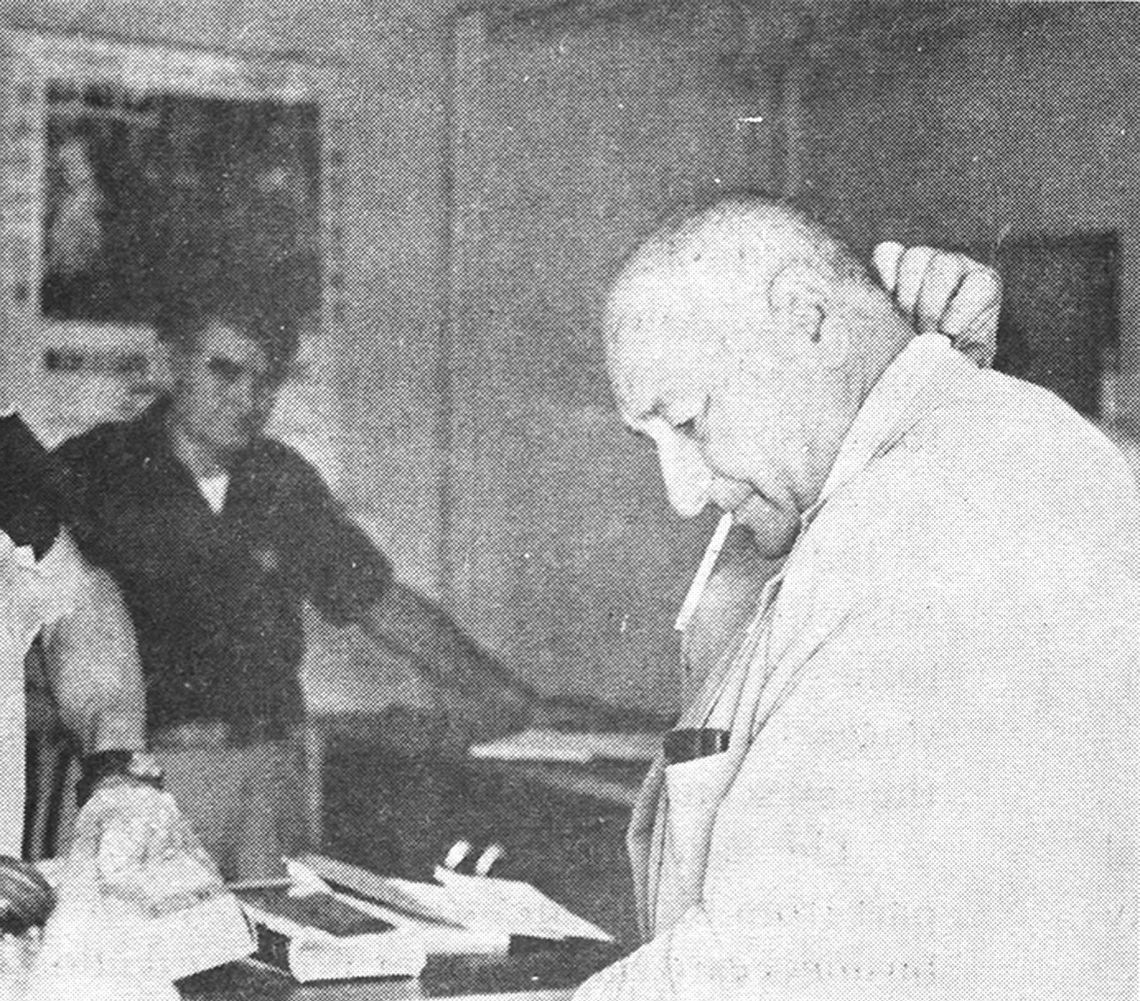

When the day came, though, there weren’t any parades or bands to greet Mel — just three reporters, one lady admirer (who remembered him as “a charming gentleman at all times”), and one small dog. Mel seemed relieved. He’d heard about the Newsweek article but hadn’t read it; he hadn’t seen any of the stories in the local press.

Mel was the last to know that he was a local folk-hero.

So Mel settled into his new quarters in the local hoosegow, awaiting his trial. What would he do there? He guessed he’d do some writing (one of his jail-keepers commented, “He has more mail transactions than we do”), and some reading.

And what would he read? What else — books about Stonewall Jackson, said Mel.

From “Update,” a Washington and Lee University admissions newsletter.

.jpg)