Editor’s note: This article was written by Rockbridge Historical Society Executive Director Eric Wilson.

One-fifth of the way through the 21st century, we’ve come to recognize the broadening variety of tombstones and memorials, the different ways in which people have conjured their “dialogues with the dead.” And depending on our social and spiritual circuits, may even have seen some of the specific grounds, and sinking graves, that mark local memory in Rockbridge and regional cemeteries.

A stuffed animal, encased like a museum artifact in transparent vitrine, watching over the grave of the beloved, a teenage girl buried in Goshen’s Lebanon Presbyterian Church cemetery.

A flat granite grave marker in Lexington’s Evergreen Cemetery, issued by the U.S. Army and attended by a flag left on Memorial Day. It rests as one of two neighboring stones there that both institutionally and personally commemorate a Black World War I veteran who’d returned to Rockbridge, deafened by the horrors of the Western Front, only to be shot dead in the dark by a night watchman, five years later.

Broader “landscapes of the dead,” prompting a series of collective emotional effects, are mindfully framed by the Blue Ridge Mountains, the Alleghenies, the saddle of House Mountain. Diverse as the individuals they bear witness to, these wider fields collectively embrace markers that may be laser-etched or limestone-worn. The oldest stones are consistently monochrome, or mottled, while many newer ones are more colorfully motley. Many are arranged in family clusters; others front images of football uniforms worn by the recently lost, or stand graced by the more timeless, inspiring figures of classical angels, or of contemporary superheroes.

The Talk and a Walk Among Tombstones

On Sunday, April 30, at 3 p.m., the Rockbridge Historical Society’s free public program will canvas the wide range of memorial traditions and commemorative themes that have shaped cemeteries throughout Rockbridge County, and beyond.

Presenter Alison Bell, professor of anthropology at Washington and Lee University, will open the day with an extensive slideshow in the historic sanctuary of Timber Ridge Presbyterian Church (est. 1746). Adapted from her recently published book, “The Vital Dead: Making Meaning, Identity, and Community through Cemeteries,” her remarks and illustrations will be followed by a guided cemetery tour that will walk you – literally and figuratively alike – through the striking sweep and variety of tombstones and commemorative artifacts marking local and regional histories.

To complement more familiar if distant conventions of historic tombstones, inscriptions, and iconography, Bell also attends to more contemporary choices that honor the dead: “If you’ve driven by a cemetery at dusk recently, you’ve likely noticed little lights – solarpowered bulbs faintly illuminating headstones. People who’d loved the deceased installed these lights, often with bird feeders, potted flowers, and flags. Flags say ‘Happy Easter’ or ‘Welcome,’ as if the deceased are in residence, as if graves are front porches of the dead.”

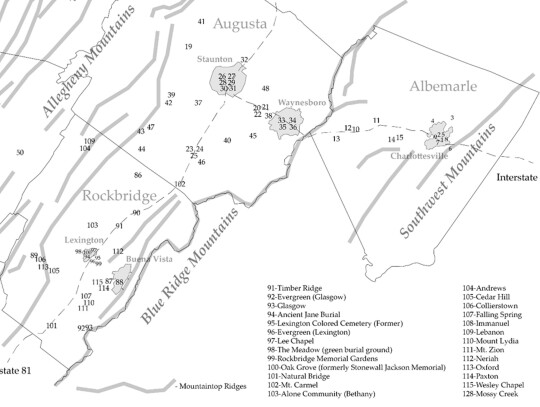

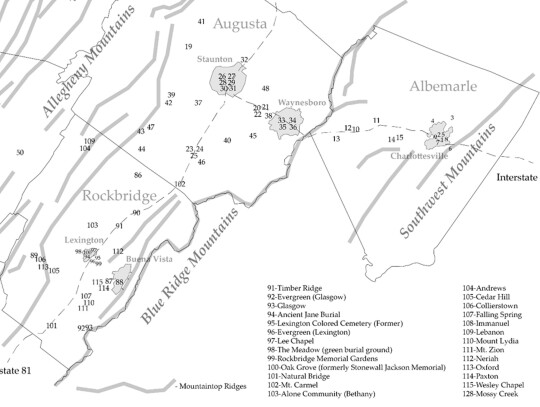

She continues by recalling even more specific encounters nearby: “Having visited more than 140 cemeteries in the Valley of Virginia – including 26 in Rockbridge County, Buena Vista, and Lexington alone – I’ve seen an extraordinary range of gifts on gravesites: Harry Potter books, lottery tickets, chewing tobacco, presents wrapped in weathering paper. People often leave photos: a winning soccer team’s 2014 photo on the grave of a woman who died in 2013. A Plexiglas box sits on the grave of a 16-year-old who died in a 1996 car wreck. Inside, a plush, purple ‘Easter rabbit’ holds an open album of photographs toward the headstone, as if showing recent family images to the beloved, deceased girl.”

After Dr. Bell’s opening presentation, those who are interested and able can extend the conversation outside, as a guided tour moves through some of the hallowed ground and grounding examples she’ll highlight. The paired slideshow and stroll will not only survey memorable examples and shared customs evident in the 20 counties she’s studied, from the southern to northern ends of the Valley. They’ll also direct particular attentions to the two neighboring church graveyards at hand, flanking Sam Houston Way, right off U.S. 11.

Resonant in the way that all burial grounds can be, the graveyard immediately outside Timber Ridge’s “Old Stone Church” (already in use before the 1777 formation of Rockbridge County, itself) stands squarely in the early footprints of associated figures and families who would shape this stretch of colonial and early America: cultivating the land, establishing new lifeways and lasting legacies, carving out their range of vital cultural forms that endure, today.

“The coffin-shaped gravestones in the McDowell Cemetery and Timber Ridge,” Bell adds, “are early regional examples of communication from the dead to the living. Remember that life passes quickly, and make choices accordingly. But recent graves similarly advise visitors, ‘Let your faith move mountains’ or ‘Don’t just stand there – Get ready!’ Graveyards seem to say that, living or dead, from the 1700s or today, we’re still part of a community: the living care for the dead’s resting places; the dead care for the living’s wellbeing. They’re still vital, cognizant, and knit into relationships.”

The Shifting Traditions

But the thematic focus here extends well beyond traditional examinations to singular stones or the resting places of celebrated historical figures.

Bell’s multi-century, cross-county approach will newly illuminate – because collectively assessed – the shifting sacred and secular traditions through which not only personal but communal histories are presented for those still living, and still to come. Family and institutional choices both draw from and adapt practices and symbols that are sometimes insistent, sometimes much subtler.

In a recent conversation, Bell added: “Seeing so many gifts on graves, and seeing so many unique images and epitaphs etched on recent markers, I wanted to understand the cultural dynamics that created them. What factors motivate mourners to inscribe gravestones not only with traditional lilies or praying hands, but also with an antique race car, or the deceased holding a 10-point buck? I’ve come to appreciate that this apparent novelty actually expresses a belief in continuing connection between living and dead, a belief with deep historical roots in our community and beyond.”

As the publisher’s overview notes of Bell’s book: “Chapters range across cemetery types, including [churches], African American burials, the grave sites of institutionalized individuals, and modern community memorials. Ultimately, ‘The Vital Dead’ is an account of how lives, both famous and forgotten, become transformed and energized through the communities and things they leave behind to produce profound and unexpected narratives of mortality.”

Tailoring her presentation to support RHS’ mission to preserve and promote local history, Bell’s presentation draws from and beyond the 100 photographs in her book. Those representative samples are themselves just part of the much wider archive captured from the nearly 150 regional cemeteries that she visited in order to provide both geographic, chronological, and cultural comparisons and contrasts. -Alison Bell has not only been a vital leader in university and scholarly circles, but through her collaborations with a number of community organizations and oral history projects, including diverse contributions through the past decade to RHS’ research, school curricula, and public presentations.

Her scholarship, teaching, and community engagement continue a wide-ranging commitment to public history advanced through a career working with historic sites, archaeological digs, contemporary ethnographies, and particular care for cultural boundaries.

At Washington and Lee she has taught courses on Material Culture, 18th and 19th century American Anthropology and History, Social Stratification and Consumption, and the Anthropology of Disability.

Her new book was supported by a prestigious fellowship awarded by Virginia Humanities.

Before the April 30 program, you can enjoy her fascinating, conversational interview with their staff, titled “Front Porches of the Dead,” at: VirginiaHumanities.org/2018/10/ Front-Porches-Of-The-Dead. -To book-end the first, plaintive memorial example summoned above, a closing snapshot offers a fitting complement, illustrating both extensions and variations in commemorative style and spirit. Bell lyrically describes the grave site of another young local girl, buried two generations earlier, in Buena Vista’s Green Hill Cemetery. “Deborah Elaine Beverly was six in 1959, when she died suddenly of illness. She’d been rushed from her Buena Vista home to Richmond’s Medical College of Virginia, but she only lingered a day. Her parents have joined her on the other side. A traditionally sculpted stone angel keeps watch at her grave, while Deborah’s face still smiles at visitors, rendered in more contemporary, photographic color. And someone recently left her flowers.”

For more images and information related to the program, see RHS Facebook or the Society’s new Instagram page @rockbridgehistory.

.jpg)