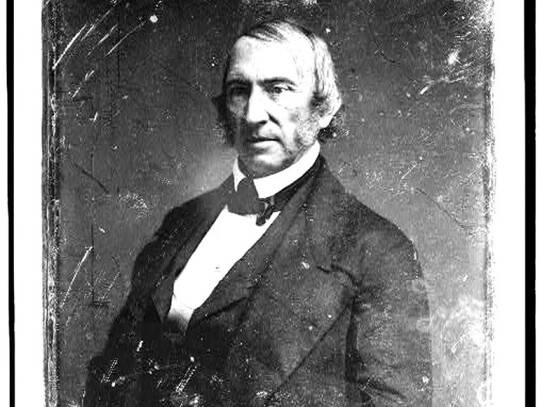

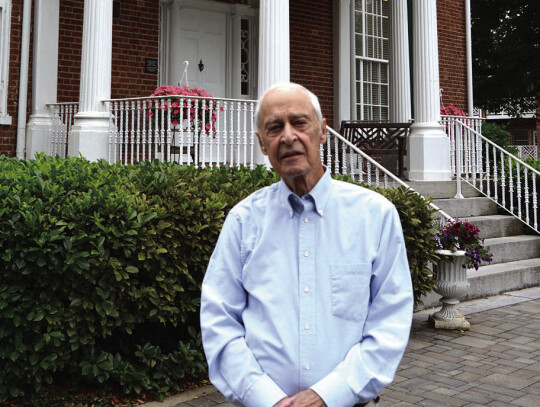

The chronicler of Rockbridge County’s history has a new book out on a prominent local citizen from the 19th century. Charles A. Bodie, author of “Remarkable Rockbridge,” published in 2012, has written a biography of James McDowell, the 29th governor of Virginia.

Many of us who live here have likely heard the name – McDowell Street in Lexington is named for him, as is McDowell County, West Virginia. There is an unincorporated community in Highland County named for him, where a Civil War skirmish took place involving Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson’s troops.

But most of us know little about the man. “James McDowell of Virginia: The Perils of an Antebellum Southern Reformer” seeks to fill in this gap in historical knowledge of one of two Virginia governors who hailed from Lexington – both in the mid-19th century. John Letcher is the better-known of the two, having served as Virginia’s Civil War governor.

Bodie believes the time in which McDowell lived might explain why this Southern reformer is so little noted by history. “Why no one has bothered [to write about McDowell] might be because of when he lived [1795-1851], in the middle years, between the Revolutionary War and the Civil War. He died in 1851 so he was not part of Civil War history. Lexington became a center for Civil War history. McDowell represented the middle period of American history that has been largely ignored for a long time.”

Although published materials on McDowell are rare, Bodie nevertheless “discovered a trove of information” about him when he was doing his research for “Remarkable Rockbridge.” There were papers scattered about in archives at Washington and Lee University, the University of Virginia and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, but by far the biggest batch of materials was found in Madison, Wisconsin. The reason the papers are there is that a traveling historian who possessed them sold them to the Wisconsin Historical Society in the 1920s after W&L and UVa had turned down the opportunity to purchase them.

During the decade or so that Bodie worked on this book, he made three trips to Wisconsin, spending extensive time there doing research. “It’s the largest collection of Rockbridge historical papers found anywhere. I spent a lot of time going through them,” said Bodie. “This was a big opportunity for me. I’m a historian and there was a trove of information about McDowell and no one had written a biography of him.”

McDowell And Slavery

McDowell’s life story offers insight into the most pressing issue of the day – slavery. As Bodie notes, much of the expansion of Virginia’s economy in the early 19th century was carried about by slavery. Though not as prominent west of the Blue Ridge, slavery was a fact of life in Rockbridge County. When he died in 1851, McDowell owned 27 slaves. His father owned 40 at his death in 1840.

At the outset of his political career, following his initial election to the House of Delegates in 1831, Mc-Dowell was seen as a progressive on this issue. Although a slave-owner himself, he favored emancipation – not of the immediate abolitionist kind espoused in the North – but of a more gradual form that would take effect over a period of time. He gave a speech on Jan. 21, 1832, on the floor of the House of Delegates advocating for gradual emancipation.

This session of the General Assembly became one of the most consequential in its history, as an open debate on the question of slavery was held for the very first – and, as it turns out, last – time prior to the Civil War erupting nearly three decades later. The debate came on the heels of the Nat Turner slave insurrection in Southampton County the previous August. Fears of further uprisings put the question of slavery’s future foremost in the minds of legislators.

A third of the Assembly’s members that session declared themselves in favor of emancipation. McDowell’s speech on the subject “was impactful,” said Bodie. As for the specific details about how emancipation could be achieved, “he was squirming over how to do it. He didn’t want to bankrupt the state. That would have happened if the owners of slaves were paid the millions of dollars that the slaves were valued at. It’s been said that the value of slaves exceeded that of all of Northern industry. There was a very big cost to it. That explains why the South was reluctant to give it up. It was embedded in everything they did.”

Many feared emancipation. “There was a general feeling among Whites at the time that Blacks were not of the same status.” Eastern planters who were in the majority in the legislature were greatly dependent on slavery for their livelihood. “They made a defense of slavery and con- trolled the votes. [The General Assembly] never tried to abolish it again before the war came along. The issue controlled so much else of what was going on.” As for McDowell? “He gave up on being a progressive very quickly.”

In fact, later in his political career, McDowell delivered a speech in New Jersey at his alma mater, Princeton University, in which he lambasted Northern abolitionists. “The speech was well received,” said Bodie. “The message was to ‘Leave us alone. We’ll figure it out.’ He favored dispersing the slaves through other territories. ‘Slavery would eventually die out.’ Of course, he didn’t address the fact that cotton plantations couldn’t be put in Arizona.”

The threat of uprisings led to unease among slave owners and their families. This is reflected in letters between McDowell and his wife, Susan, said Bodie. “She wrote that she was tired of locking doors, tired of seeing Black faces. She feared them. They [the McDowells] were prisoners of their own system. They couldn’t get out.”

Life In Rockbridge

McDowell was born at Cherry Grove, an estate of his father’s that was not far from present-day Fairfield. Just two generations removed from Scots-Irish pioneer-settlers, his birthright was of a well-todo landed gentry. He attended school in Greenville, Brownsburg and at Washington College before being sent North to be educated at Yale University and ultimately graduating from Princeton.

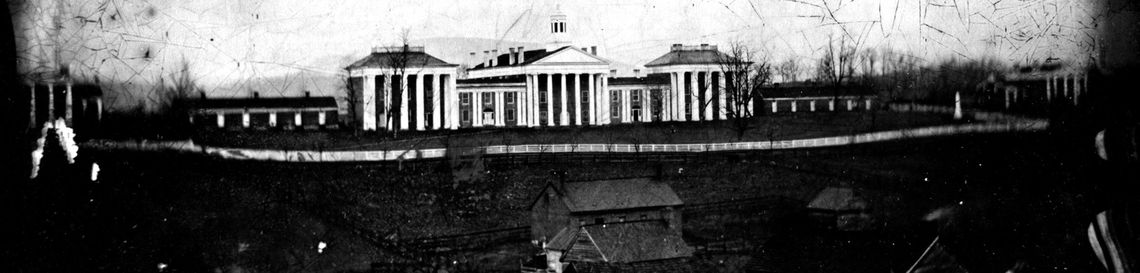

McDowell’s father of the same name made his mark here as the surveyor who drew up the plans for the streets of Lexington. In 1819, the elder McDowell purchased 328 acres east of town for $1,000. His son built a “large and commodious” plantation house there in 1827 for $1,500. The home was named Col Alto – meaning “high hill” in Italian. Surrounded by fields and woodlands, Col Alto became a working plantation for the younger McDowell. (The Col Alto mansion survives to this day. The fully restored structure is now part of a Hampton Inn.)

First cousins James and Susan McDowell married in 1818 when he was 23 and she was 18. She was the daughter of Gen. Francis Preston of Washington County. Her mother was the daughter of Revolutionary War Gen. William Campbell and Elizabeth Henry, sister of Patrick Henry. The merged families included many prominent members of high Southern society – Bentons, Prestons and Breckinridges. A number of the male family members ascended to high office.

As a young attorney, Mc-Dowell played a role in writing up a will that would have major implications for Washington College. He helped prepare the will in 1825 for wealthy Rockbridge County landowner John “Jockey” Robinson, who bequeathed his entire estate to Washington College. Robinson owned hundreds of acres in Hart’s Bottom along the North River in what later became the site for Buena Vista.

Instructions in the will were to keep all of the slaves “together with their increase … for the purposes of labor for the above lands for the space of 50 years after my decease.” Upon discovering debts of the estate, the trustees for the college disregarded the directives in the will and arranged to sell the entire estate – lands, livestock and slaves. By 1835, auctions had almost completed the process.

An incident involving Mc-Dowell’s family that Bodie devotes some attention to is the brief marriage and acrimonious divorce of McDowell’s daughter Sally to Maryland’s governor, Francis Thomas. The man was 20 years her senior and obsessively jealous and controlling. He made wild accusations of infidelity that drove Sally back to her parents’ home. Bitter divorce proceedings ensued, and dirty laundry aired. Everyone involved seemed to reach the conclusion that Sally’s husband was mentally unbalanced.

One interesting anecdote that Bodie relates involved McDowell, then governor of Virginia, having an altercation with Sally’s husband at a stagecoach depot in Staunton: “The governors glared at each other and exchanged angry words. McDowell smacked Thomas with his umbrella, and incredulous onlookers separated them.”

McDowell’s Legacy

McDowell served several terms in the House of Delegates during the 1830s. He both won and lost elections. “He kept bouncing back from each defeat,” remarked Bodie. “One wonders why he didn’t just quit seeking elective office.”

McDowell was chosen as governor of Virginia in 1843 by members of the House of Delegates. He served a single three-year term and was subsequently elected to Congress, serving for the remaining five years of his life.

As a delegate, McDowell introduced a bill to establish Virginia Military Institute. After he suffered one of his electoral defeats, someone else picked up this legislation and successfully pushed it through to establish the military college and armory in Lexington. McDowell was on VMI’s first board of visitors. He also served on Washington College’s board. He helped to establish what is now the Virginia School for the Deaf and the Blind in Staunton.

McDowell was a strong proponent of education, and all nine of his children had at least some college, which was quite remarkable in that era. As a legislator, he proposed a public education system in Virginia that didn’t come to fruition until many years later, after the Civil War, when Republicans took up the issue and successfully saw it through during the Reconstruction years.

McDowell advocated for making major improvements to transportation so that producers in the Western counties of Virginia could get their products to markets in the east, including ports for overseas trade. He was a proponent for the James River and Kanawha Canal that was developed as far west as Jordans Point at East Lexington.

So, while it can be said that McDowell didn’t have a very big impact on the biggest issue of the day, slavery, he did live an impactful life that is well worth remembering, with significant contributions in the areas of transportation and education.

“James McDowell of Virginia: The Perils of an Antebellum Southern Reformer,” was published in 2023 by Lexington Books, an imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group Inc. The book can be ordered at https://Rowman. com/Lexington. To get a 30 percent discount, use code LXFANDF30 when ordering.

.jpg)