Editor’s note: The following article was written by Eric Wilson, executive director of the Rockbridge Historical Society, which partnered with the Rockbridge Regional Library and local churches to organize the Black History Month program described here.

For many, faith is that thing that can’t be materially touched. Something, in many traditions, that is unbounded, if paradoxically, a powerful bond. And yet, in the arcs of everyday life, faiths are variously tied to other persons, places and things: families and fellowship; churches and safe havens; self, and spirit, no less.

On Saturday, Feb. 24, at 3 p.m. at Lexington’s First Baptist Church, a special program invites the entire community to explore the connective orbits constellated by specific people in local history, in a transformative window of time.

Capping Black History Month, “Bond of Faith: The Devotion of Sam Williams” explores the ambitions and commitments of a once-enslaved iron worker at Buffalo Forge, whose decades in Rockbridge before and after emancipation found him steering his family through emerging opportunities, sudden loss, and new loves. In the new arcs of freedom, he also helped to establish the Buffalo Colored Baptist Church in 1871.

The program extends from last year’s collaborative, community-sourced program in Glasgow, “Bond of Family: The Legacies of Garland Thompson.”

This year’s event again partners the Rockbridge Regional Library with the Rockbridge Historical Society and Union Baptist Church, along with other local history organizations, and church leaders, choirs and soloists. In addition to spirited music, personal reflections, and historical exhibits, the program includes both pastoral and scholarly remarks on histories of the Black church, and on the traditions of African American spirituals.

Penny Dudley, program organizer and manager of Rockbridge Regional Library’s new Local History Center, reflects on these collective goals, noting that the narrative of Sam and Nancy Williams (and other women and men enslaved and freed in Rockbridge) “gives us identity and appreciation for our place in a rather long, complex, and wonderful human story as it connects, empowers, and inspires.” She also invokes the verses of prize-winning young adult novelist Ibi Zoboi: “The people will gather the pieces of fabric/Cut, torn, shredded, and made unrecognizable/ By the storms of time – /To sew together a tapestry of their stories, /One fine quilt, /A blanket for the children/To keep them warm, protected, and safe. /The people remember to always have faith.”

One of the afternoon’s highlights will be a virtual appearance by Williams College Professor of History Charles Dew. In 1992, Dew published the path-breaking and still foundational book, “Bond of Iron: Master and Slave at Buffalo Forge,” from which many of the historical accounts below are drawn.

Another notable moment in the program will signal the upcoming land transfer between descendants of the last slaveowning family at Buffalo Forge, and Glasgow’s Union Baptist Church. The Reconstruction-era Buffalo Forge Colored Church that was first built on that ground would soon be renamed Mt. Lydia Colored Baptist Church. After the building burned a century ago, the congregation would effectively fold into the Baptist church in Glasgow, of shared denomination, just four miles away. Thanks to the efforts of a new historical foundation dedicated to preserving Mt. Lydia Cemetery, negotiations are proceeding to confer the historic property to Union Baptist.

As president of that foundation, and descendant of enslaved-and-free families at Buffalo Forge, Brandall Branch affirms, “This is our history. We have to learn from it and move forward, and we have to hug and love each other.”

Advancing that same purpose and care – and as a descendant of one of the families who’d owned the property and people working at Buffalo Forge – Vice President Susan Brady echoes, “This opens things up: Conversation. Communication. Friendships.”

The Williams Family

A few years before publishing “Bond of Iron” in 1992, Dew had drafted an article entitled “Sam Williams: The Life of an Industrial Slave in the Old South,” its manuscript now part of the Brady Family Papers in RHS Collections, held at Washington and Lee. Concentrating a range of the biographical sources and larger themes that would fan out into his 400-page book, Dew’s essay opens resonantly, respectfully, reflecting on the challenges and rewards of such a project: “The public record is sparse indeed on the life of Sam Williams and his family. Nor did he leave letters, diaries, journals, or other manuscript materials … Yet it is possible to discover a great deal about Sam Williams and his family. They deserve our attention not only because they were people caught up in the American system of human bondage and thus illustrate something of the nature of the antebellum South’s most significant institution.

“They also warrant our best efforts at understanding because, if we look carefully, we can catch at least a glimpse of them as something more than representative historical figures,” Dew continued. “We can see them as men and women who lived out very human lives despite the confines and cruelties of their enslavement. Their human qualities, their love and affection, their joys and sorrows, their times of trial, and moments of triumph, show through to us, imperfectly, to be sure, but visible nonetheless, in spite of their inability to speak to us through traditional historical sources.”

For broader portraits of the Williams’ lives, and the many other free, enslaved, and emancipated Americans living on the “industrial farm” and plantation at Buffalo Forge (variously owned by William Weaver, his partner Thomas Mayburry, and D.C.E. Brady, husband to Weaver’s niece), refer to Dew’s extensive book, or a shorter talk that Dew delivered as an RHS program in the front yard of the Brady estate in 1994, then published in RHS Proceedings (see tinyurl.com/RHS-Master-Slave-Forge-Dew).

With ancestors from Rockbridge and Botetourt counties, and his parents also enslaved at Buffalo Forge, Sam Williams Jr. (1820-1889) married Nancy Jefferson (no birth date recorded, died 1888) in 1840. Their first four years of marriage brought them four daughters: Elizabeth (or Betty, named for Sam’s younger sister), Caroline, Ann, and Lydia. But no other children would follow, and tragedy would ravage the young family, with illnesses that broadly stalked the 19th century.

On Sept. 24, 1862, Betty died during a diphtheria outbreak that swept across the Buffalo Forge community, free and enslaved alike. On Oct. 9, 1864, the Williams’ 20-yearold daughter Lydia would die of typhoid fever, only two days after her sister Caroline gave birth to a daughter, Maydelene Lydia Williams: another “tribute name” that would live on despite her aunt’s premature death. In the 1880 census, Maydelene Lydia, age 15, would be noted as living near Natural Bridge, with her grandparents, Nancy and Sam.

In joint witness, “Lydia” would also become namesake for the 1871 church established on Forge Road, a mile south of the Brady farm. The building burned down over a century ago, now survived only by the Mt. Lydia cemetery. With burials continuing there through at least 1930, it remains the resting place of Sam and Nancy Williams, buried alongside other relatives, neighbors and congregants from Buffalo Forge and southern Rockbridge.

Finance And Faith

Like most enslaved men and women in Virginia who were legally barred from learning to read and write, Sam and Nancy Williams were illiterate, their names on surviving financial documents noted by an “X” rather than signatures in their own hands.

Nevertheless, that legallyrecognized mark survives as a clear signal of negotiated opportunity and responsibility. More surprisingly, Sam’s authority is serially inscribed in the records of the Bank of Lexington, where both he and Nancy held separate savings accounts in the 1850s; at one point, their combined deposits totaled over $2,500, in today’s dollars. These holdings – approved by their owner, William Weaver, as well as the town’s white bankers – were funded by “overwork” bonuses they’d earned, and the accruing interest that gradually increased their capital.

Sam’s skill and experience brought him power and strategic choices. Once, he chose to sit out from work for a full month. His “production value” could also provide leverage to prevent the separation or sale of his family. The volunteered efforts for extra pay, and the economic counter-pulls in such exchanges, complicate narratives of power and opportunity, unequal as they ever and obviously are under a system of chattel slavery.

During the profound transformations that came in the early wake of emancipation, we can see interesting variations in freedmen’s labor contracts with D.C.E. Brady at Buffalo Forge: some with monthly payments, some yearly. In 1867, Sam Williams’ salary was tied to his output: “four dollars for each ton of bar iron.” But for additional tasks on the farm, he was also rewarded with a “House, and free fuel,” a pen with three hogs, and a lot to raise corn to feed them.

Other workers negotiated some of these provisions, or different ones, according to different skills and family arrangements, perhaps even personal preferences, in the new landscapes of freedom.

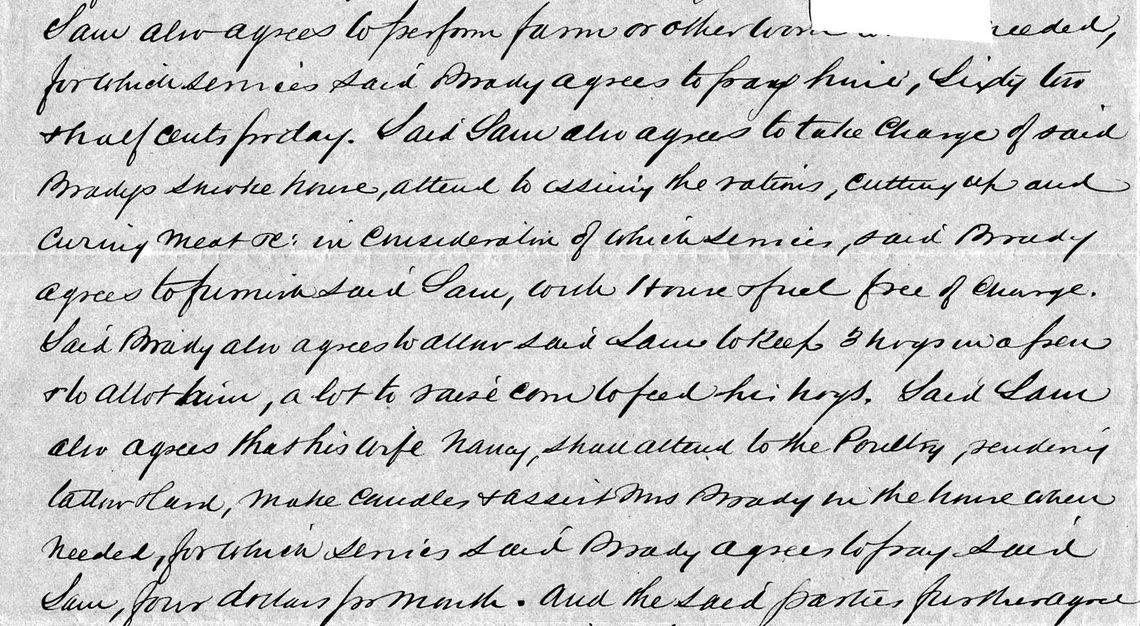

In the same contract, his wife’s more “domestic” labor was also itemized: “Said Sam also agrees that his wife Nancy shall attend to the Poultry, rendering butter & lard, make candles & assist Mrs. Brady in the house when needed, for which services said Brady agrees to pay said Sam, four dollars per month.” (Note, to be sure, this is a contract and payment between men, for all the work the two women jointly contribute.)

To further compare and contrast the Williams’ terms with a dozen others – all signed by Sam’s male peers on New Year’s Day, 1867 – see the digitally scanned manuscripts and transcripts from RHS Collections at tinyurl.com/RHS1867-FreedmensContracts.

Beyond the interest he often drew off, while preserving a neat $100 balance of sustaining principal, Sam Williams’ bank account – the calculus of his extra labor, and faithful care for his family – also positioned him to become a founding trustee of the Buffalo Forge Colored Baptist Church. For $20, the group purchased a half-acre lot from Brady in October 1871, only six years after the close of the Civil War. Additionally, the trustees and community had collectively amassed a remarkable $307.29 to build a church, schoolhouse, and cemetery plot where Sam and Nancy Williams and others still lie – some with still-legible headstones, other names lost to history.

Together, these personal and collective commitments signal a trinity of faith – in spirit, in family, in self – and in the social relationships and institutions that Sam Williams and others grounded their lives in. Through the arc of centuries, some expressions of faith are vividly recorded through writing: letters and journals; poems and sermons; baptismal records and marriage vows; recorded last words and wills.

But there are other means to assess and attribute such sentiments, and commitments: the lyrics or even nonverbal melodies and harmonies of hymns, spirituals, and songs. Or sacred rites, such as funerals that tear families apart, and marriages that expand them. Whether guided by litany, credo, or ritual prayer, private devotion bears its own unspoken witness: sometimes observed in the segregated balconies of the antebellum era; or newly inspirited, in the pews of the many other Black churches that established themselves in Rockbridge in the late 1860s and 1870s.

Historical Exhibit

The exhibit now on display in the Rockbridge Regional Library accounts for several of Sam Williams’ recorded possessions, bought while still enslaved: his pocket watch, a mirror, and an expensive $20 blue coat bought on Christmas Eve, 1844, to be worn at his baptism, examination, and confirmed affirmed membership – still over 20 years before becoming a freedman – at Lexington Baptist Church (now Manly Memorial Baptist).

Together, these distinctive objects attest to everyday utility, pride of display, affection for his wife and children. Sam and Nancy Williams’ investment in a new, neighboring church was even more purposeful and lasting. They herald a shared “Bond of Faith” that joined many others, and still resonates today, for descendants, descendant congregations, and the legacies of local history we can still explore, in new lights, and appreciation. (See rrlib.net for more on exhibit dates, details, and library hours.)

.jpg)