Sunday Program Discusses Recent DNA Discoveries

Editor’s note: The following story was written by Eric Wilson, executive director of the Rockbridge Historical Society, with contributions from the team planning the March 10 event described here.

The genetic reports came back in December 2023, and the results were instantly surprising.

The telling new markers came from the chromosomal strands of a left molar, “the tell-tale tooth,” that had once belonged to a young woman, then and still anonymous. Her remains were either humbly buried or left in the ground two centuries ago, before their re-discovery in 2008 during a major construction project in downtown Lexington.

But for all the mysteries that still remain, these biological threads newly point to a human story anchored even further back in Rockbridge time than previously projected, perhaps into the 18th century. And they appear to tie this woman’s own life, as well as her longer ancestry, more directly and definitively back t o A frica. A dditional genealogical and genetic inquiries still lie ahead, with some promising prospects.

But the next stop on the roadmap points most immediately to a program at Lexington’s Community Center, 300 Diamond St., this Sunday, March 10, at 3 p.m.

Titled “Miss Jane’s Journey: New DNA Discoveries,” the free event invites community members to learn more about these new findings during Woman’s History Month, as jointly presented by civic leaders, historians, and scientists from the city of Lexington, the Rockbridge Historical Society, Washington and Lee University’s Sociology and Anthropology Department, and University of California at Santa Cruz. I t also builds on the communitywide care and momentum witnessed at the May 2019 re-interment of Miss Jane‘s bones at Evergreen Cemetery.

The gathering Sunday will include a live Zoom presentation by the forensic scientists from U.C. Santa Cruz’s Paleogenomics Lab who assayed the tooth and compared their findings to a host of internationally sourced data sets. Illustrated for the general public, their discoveries and continued inquires quite literally put new points on the maps of local and global history. These now-known data points, and new hypotheses, are helping to more fully sketch the personal experiences – and social and cultural connections – of the figure to be honored here again, bridging Women’s History Month and Black History Month.

The Find

During the construction of the new Rockbridge County Courthouse in 2008, a full set of skeletal remains was found where the parking deck now stands, just behind the properties of the Rockbridge Historical Society.

W&L anthropology professor Dr. Alison Bell reflected: “That discovery was 16 years ago, a time when some of our current W&L students were starting kindergarten, and others were still toddlers. A few of them had probably already lost their baby teeth.”

Drs. Donna Boyd and Cliff Boyd of Radford University’s Forensic Science Lab took custody of the bones.

In the profession’s conventional terms, she was formally identified as “Jane Doe,” an African American woman between 5’6” and 5’9” tall. She died young, between 17 and 23 years old.

Lexington had always been envisioned as the lasting point of return for “Miss Jane” (earlier she had been more regularly referred to as “Ancient Jane,” fronting her lived era, more than her gender). But negotiating logistics, planning, and securing funding took time. In 2019, new pieces fell into place, with the Boyds releasing the remains to members of the Lexington Police Department, who brought her back with care and the support of the city.

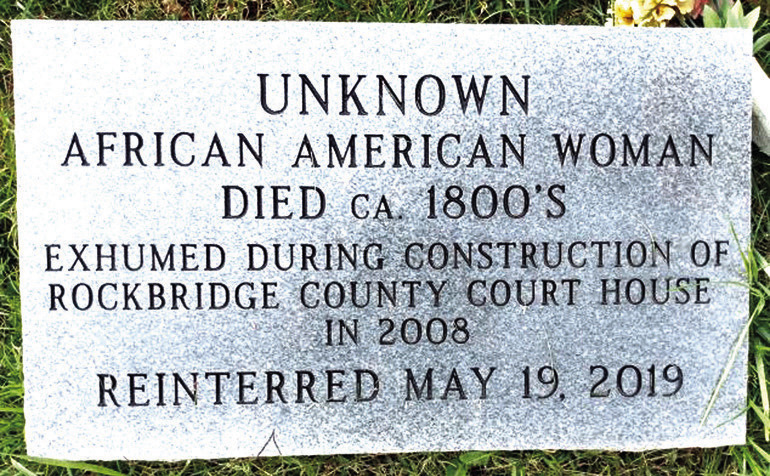

Members of the Lexington community contributed to a bank account for her reburial. A coffin was handcrafted from local wood using 19thcentury t echniques. T he city donated staff time and a burial plot on the western slope of Evergreen. Hamric Memorials contributed a gravestone, reverently inscribed, “Unknown African American Woman, Died ca. 1800’s.”

The New Findings

While the surviving bones were being laid out at Randolph Street United Methodist Church that May afternoon in 2019, two loose teeth were collected before the coffin’s final cushioning was added, the lid nailed shut, and borne to her burial by a horsedrawn carriage and buckboard, with police escort.

One tooth is stored at W&L for potential future analysis. The other was submitted to the Genetics Institute and Paleogenomics Lab at U.C. Santa Cruz. Since then, Dr. Lars Fehren-Schmitz and Kalina Kassadjikova have combined their expertise with the new techniques and analysis of colleagues’ well-tested data across the globe.

Their core findings signal two important shifts, and focal points: one that is genealogical and geographical, and the other, more chronological. In layman’s terms, they will share their insights with the general public for the first time, in Lexington. In live-Zoomed remarks, they will discuss and field questions about Miss Jane’s “origins,” and how her DNA compares to that of other populations in Africa and North America.

The techniques they’re using were not available five years ago, and additional methods continue to emerge. Next steps might reveal not only more specific information about her ancestry, heredity, and ethnicity, but her diet, migration and when she died (via carbon dating). Illustrating both the sweep and specificity of their methods, data, maps, and comparative studies, their December report notes that “Ancestry analysis was conducted against global and Africaonly reference datasets to establish Ancient Jane’s genetic origins.”

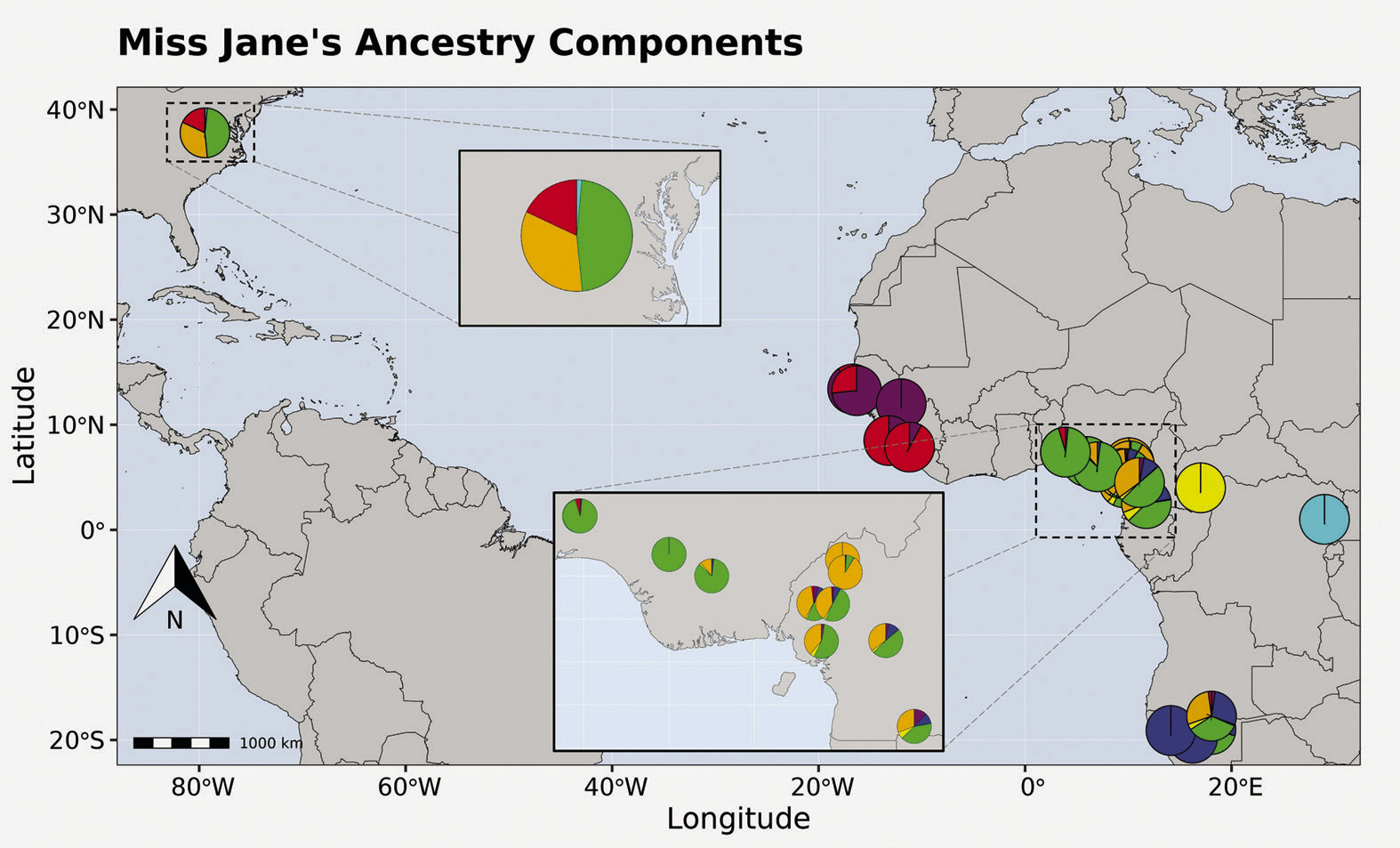

The maternally descended through-line they’ve analyzed (mitochrondrial haplogroup L2c) “is estimated to have emerged in West Africa and is today found in highest frequencies in the same region, notably in Senegal, Cape Verde, and Guinea-Bissau … The role of these regions in the transatlantic slave trade has been firmly established, and the contribution of these populations and the presence of this haplogroup among African descendants in the Americas has been noted across the continents.”

Moving beyond contemporary national boundaries to examine traditional cultural groups, they add: “There is a particularly high affinity between Ancient Jane and groups from modern day Cameroon (Lemande, Bakoko, Bangwa, Aghem, Mbo), Nigeria (Esan, Yoruba), and Sierra Leone (Mende).”

Even more strikingly, the genome of Miss Jane reveals “strictly African ancestry with no European or other non-African genetic contribution.”

In more conventional terms: her 100% African markers reveal no “white” or indigenous ancestry that might have emerged in colonial North America, or the early decades of the American Republic. In short, she would either have been born in Africa herself, or to parents whose own maternal and paternal lines were uniformly African in their descent.

In effect, that definitive identification unsettles some earlier assumptions not only about ancestry and migration, but about timelines, however long or briefly Miss Jane may have lived in Rockbridge.

Working around the historical benchmarks for the African slave trade (and the intra-American slave trade that grew rapidly in Virginia and nationally), it now seems highly likely that the consistent character of her Afrocentric genetic code would push her birth and death towards earlier years, however anchored on either or both sides of the Atlantic.

Knowing she was only about 20 years old at death, and with the transatlantic slave trade legally abolished in the United States in 1808, her date of birth logically shifts earlier: whatever personal or ancestral migration likely channeled through the slave ports of West Africa, toward her eventual arrival in Rockbridge. Perhaps she even traveled with other members of her family (although further attempts at proximate excavation were not made at the garage site, when her bones were exhumed).

This raises the prospect that Miss Jane could even have been born in either Africa or America in the 18th century, with at least some stretch of her life here during that first post-Revolutionary generation, when Rockbridge and Lexington were chartered in 1778, on the edges of a colonial- indigenous frontier. It’s also possible she was born in the United States to two parents of full African heritage, without European or Native American strains of their own. But the longer that time reaches past 1808, the more likely that strains of genetic admixture would become evident.

A final dimension here doesn’t point back into this young woman’s past, as much as it does to our own, reckoning with the possibilities of descendant lines. It’s important to continue exploring what brought her migration here, as it is for all Rockbridge immigrants and descendants. A nd it would b e compelling to discover what may have contributed to her young death: disease, diet, childbirth itself?

The question of whether or how many children she may have given birth to is partly shaped by the age at which she was projected to have died (age 17-23). The forensic analysis of her own DNA cannot reveal the history of childbearing, in the ways it might identify other hereditary conditions. But comparative assessments to other living subjects, or population samples, might provide lateral clues.

A then-relevant question is whether any surviving offspring or close relatives may have lived or stayed here, through the local constraints or new opportunities that marked the second half of the 19th and 20th centuries. The seismic turns of emancipation would drive their own new journeys and settlements. A half-century later, the tidal forces of the Great Migration would exert new regional and national pulls in the wake of World War I, along with shifts from the agrarian South to economic and social opportunities in the more industrialized North. Where “Miss Jane’s Journey” might have keeled, beyond her own short life, is still an open map.

Steps Forward

On March 10, Lexington Vice Mayor Marylin Evans Alexander will revisit some of the momentum that has spurred meaningful community interest in the five years since the Evergreen ceremony on May 19, 2019.

She continues to acknowledge how much of that drive came from Dr. Theodore C. DeLaney, Lexington native, and W&L history professor, who died in December 2020. Beyond their shared roles as civic and educational leaders, both Alexander and DeLaney descend from ancestors who’ve lived in this county across three centuries, with DeLaney having hoped to extend genetic analysis that might identify local ties, through the revelations of a single tooth.

Last week, Alexander expanded on her remarks at that widely attended ceremony in 2019: “There were so many prominent citizens buried later here, any one of whom could have been the central influence on someone’s life. B ut i t w as M iss J ane, likely the oldest buried there, the one no one knew of, too young to have had any significant achievements in her short life, who has contributed to this community in one of the most significant ways possible.”

The vice mayor explained further: “Mindful of the civic advances in Lexington since the burial of Miss Jane, I cannot help but think her existence – prompting so many hearts and minds – helped catapult these significant changes to bring equity to this final resting place.”

A question-and-answer session this Sunday will invite attendees to engage the varied expertise of scientists, anthropologists, and local historians. Several community members have previously asked about prospects for researching potential descendants who may still be living today, here or elsewhere. So the pair of genetic researchers will also discuss some of the advances, limits and options emerging through more sophisticated laboratory research, or those increasingly accessible through commercial ancestry tests like 23andMe.

A doctoral candidate in anthropology, Kassadjikova said in a recent planning session for Sunday’s event, “It’s important for me personally, and perhaps scientifically, to feel the connection to the people and community to whom this individual and cultural work is significant: to know that there is community support, interest, investment for the research. I hope that our current results and presentation will continue to foster this sense of community, and continue to try to answer the questions that neighboring citizens think worthy to explore.”

For more information on the program, or how to contribute financially to the account that still supports this ongoing research and commemoration, send an email to Bella@wlu.edu or Director@RockbridgeHistory. org.

MAPPING patterns in Miss Jane’s ancestry, which is 100 percent African, color-coded pie-charts reflect how common particular genetic strains are in different parts of Africa and in Miss Jane’s DNA. New results suggest the most substantial proportion of her ancestry (green) derives from what is now southwest Nigeria, particularly the Yoruba and Esan peoples. Second most common are groups from western Cameroon (in orange). (Map prepared by Dr. Lars Fehren-Schmitz and Kalina Kassadjikova)

DURING the 2019 reburial of Miss Jane, attendees left flowers on the coffin, which was carried from Randolph Street United Methodist Church to Evergreen Cemetery by a horsedrawn carriage and buckboard, with police, VMI cadets, and civic and university representatives as pallbearers.

THE GRAVESTONE for Miss Jane was placed during her reburial at Evergreen Cemetery in May 2019.