A Historic Loom, Live Demonstrations At RHS Museum

Editor’s note: This article was jointly written by Rockbridge Historical Society Executive Director Eric Wilson, and the exhibit curator, Frances Richardson.

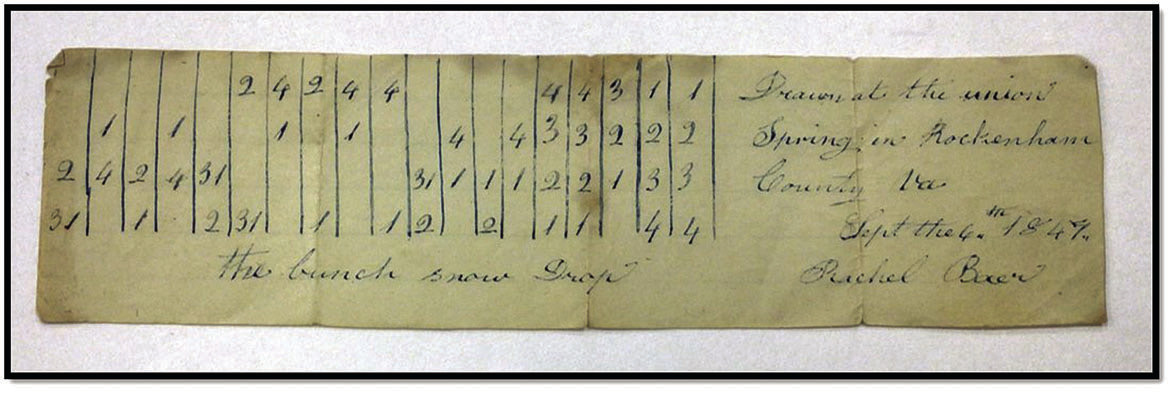

On Sept. 6, 1847, 21-year-old Rachel Baer, who lived with her family near Goshen at Panther Gap, carefully copied out a weaving pattern in her beautiful script.

She was at Union Spring in Rockingham County when she wrote the pattern onto a 6-inch strip of paper, marking its very specific place and date. But we know she brought it home to her family farm, in the northwestern corner of Rockbridge County. There, she shared it with her mother and sisters and kept it along with 20 other weaving patterns the family collected over the years. The girls’ descendants donated the papers to the Special Collections Library at Washington and Lee University in 1974.

With her own evident sense of tradition, we don’t know whether Rachel could have imagined that, more than 150 years later, a group of inquisitive weavers would join together to reproduce all the Baer sisters’ patterns (weavers call them drafts). But that’s what happened, and the results of these new “Sisters at the Loom” are now on display at a new exhibition, “Rockbridge Weavers: Families and Fabrics in the 19th-Century.”

Re-Weaving the Past

The exhibit opens on June 29 at the Rockbridge Historical Society Museum at 101 E. Washington St., Lexington. On Saturdays and Sundays, noon to 4 p.m., and continuing through the rest of the year, visitors can examine the mechanics of a 19th-century wooden loom, once used for these same techniques. They can also examine period textiles and modern samples, drafted from the specific codes recorded in these fragile paper patterns, scripted two centuries ago.

To make the requisite craft and patient labor more evident, regular demonstrations have been arranged by exhibit curator Frances Richardson and her fellow weavers. Many of those reproductions now hang on the walls of the museum, along with the artists’ own reflections on the process, past and present.

Historic maps, account books, and other artifacts further illustrate central contexts of local history and communities, with many names noted in the exhibit still familiar here today. Other artworks and furniture, texts and textiles featured in the museum further complement these displays by highlighting different social classes, generations, and material forms that bring 19thcentury Rockbridge more fully to life.

The transitions between documentary research, new loomwork, and public outreach were spurred just before the pandemic in 2020 when Richardson examined a coverlet at the RHS Museum, donated by the local Womeldorf family.

Questions about patterns and technique led to new insights from weaving guilds, inquiries into local archives, and shared efforts to bring those early American textile patterns to new life. In 2023, Washington and Lee University hosted an exhibition titled “Sisters at the Loom,” featuring this collaborative work, from which this exhibit has been drawn and expanded.

In a caption next to the 6-foot-tall loom she’s loaned to the exhibit, Richardson reflects, “Just as notes on a staff can be turned into beautiful music, so the hatch marks and numbers on an old draft can be turned into beautiful textiles. When a draft has pin holes in it, it means it has guided other hands. Someone before me played the same tune that I am playing. That’s magic.”

In the Remsburg Gallery, visitors can survey other profiles that spotlight today’s “Sisters” – as well as the local forebears who inspired them – jointly detailing some of the social networks in Rockbridge before the Civil War, and these contemporary 21st-century efforts.

Artistic Craft, Social Connections

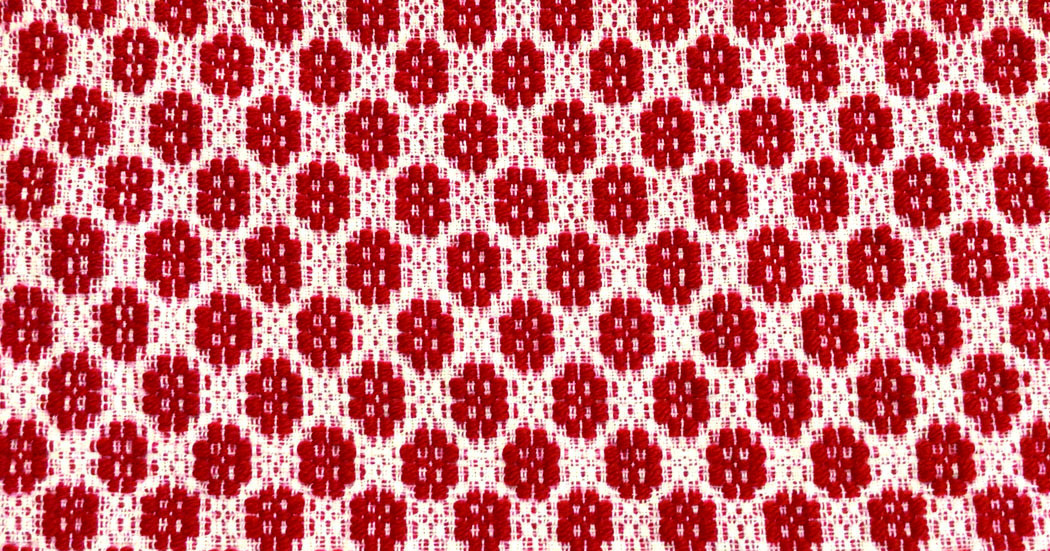

In recreating Rachel Baer’s “Snow Drop” pattern, Buena Vista weaver Catharine Hagan said she was “thrilled to be part of this collaborative work,” because it gave her an opportunity to use her modern-day weaving skills to reproduce the works of the past.

ABOVE, this 1847 weaving draft, “The Bunch of Snow Drop,” was handwritten onto paper by Rachel Baer of Panther Gap. AT RIGHT, in 2022 Catharine Hagan of Buena Vista wove this sample based on Baer’s draft. (draft is from the Baer Papers, W&L Special Collections; photo by Eric Wilson)

Rockbridge County weaver Linda Wilder also described a strong connection with the past: “It was a joy to weave a coverlet sample for this project, appreciating with each throw of the shuttle, that another woman had followed the same sequence by producing the exact same fabric that’s connected us through time.”

Weaving samples from the Baer sisters’ drafts gave insight into the kind of fabrics that were being woven on home looms before the Civil War. And we know for sure that many of the patterns were used, not just collected, because they have pinholes in them. The weavers would pin the pattern up on the loom and use pins to keep track of the weaving sequence.

Some of these drafts were annotated with fanciful titles, inviting some visual or narrative association: “Sleeping Beauty,” “Freemason’s Coat of Arms,” “Double Compass,” “Guinea Hen,” and “Jackson’s Windows.”

As the reproductions of these patterns samples came off the looms, the modern weavers’ curiosity grew even more, threading into new directions.

Why did the Baers keep the drafts? Where did the Baers get their weaving supplies? Were they the only ones weaving? Did they make all the cloth they needed, and if not, how were their other textile needs filled? What role did the textiles play in the family’s life?

To answer these questions, Richardson and W&L Special Collections staff turned to the Baer family papers and ledgers of local general stores. The answers revealed the vibrant social and economic lives of farming families, especially women, in Rockbridge County before 1850.

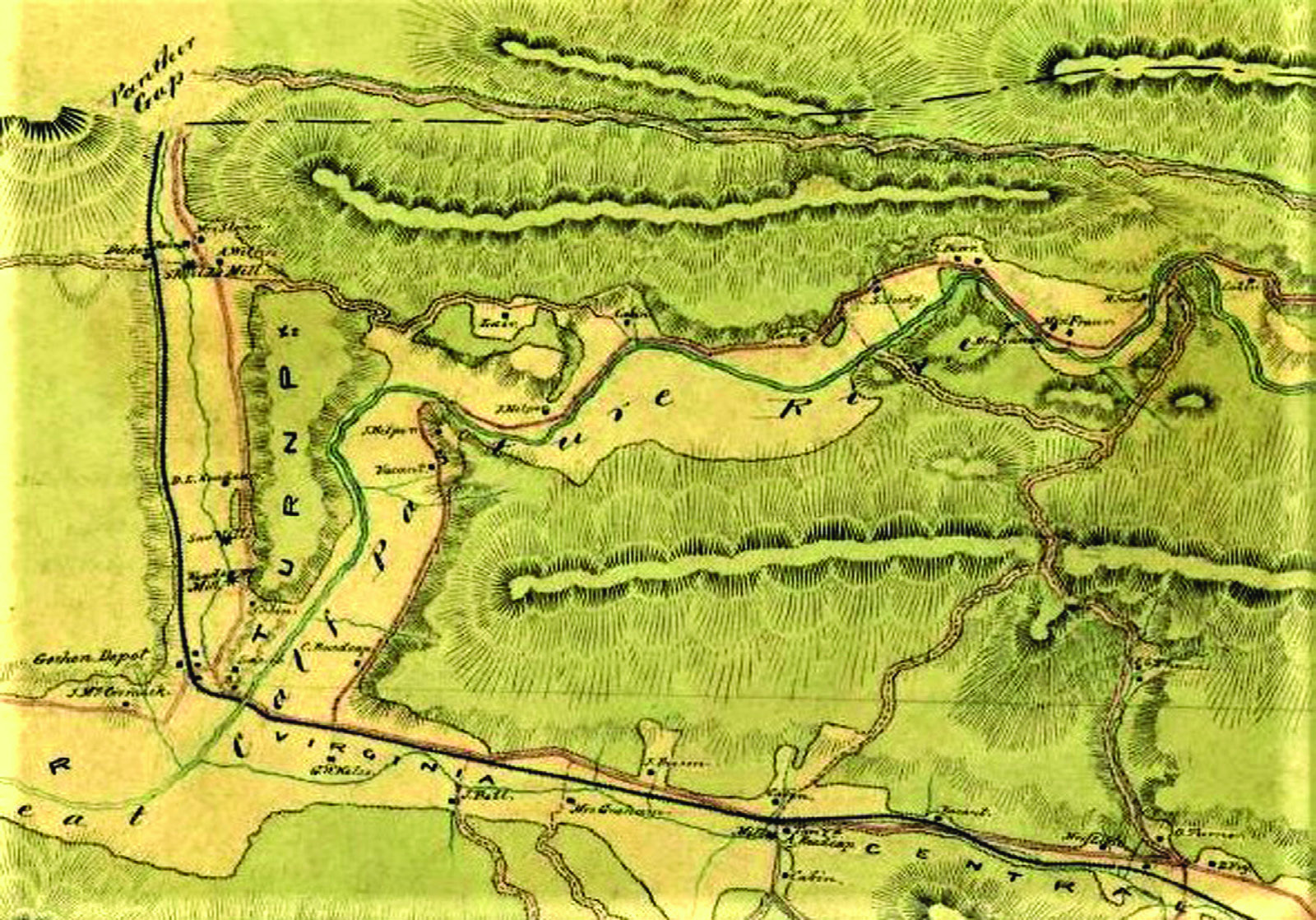

The fabrics woven from the drafts are fancy. They were used for table linen, towels, and bedcovers, called coverlets or counterpanes. The drafts were for fabrics that the weavers were proud of, that showed off their skills, and that most likely were used as gifts for newly married relatives, or as contributions to a hope chest. That’s one reason they kept the drafts, but many also have the names of the women who contributed the patterns: Charlotte Welchhans, Mary Maggard, and Mrs. Young were neighbors or relatives. So it seems likely that the drafts were important as commemorations of community and family ties. -Nowadays, Panther Gap is quiet, literally the gap in the Alleghenies where Va. 39 snakes from Goshen to Warm Springs. But in the 19th-century it was a lively place, its range of farms complemented by mills for making flour and carding wool, at least two general stores, and a post office.

In the ledger of Wise’s general store from the 1830s, we see entries recording Joseph Baer, the girls’ father, buying cotton yarn of a suitable weight for weaving, along with indigo and madder, dyes to create blues and reds. There were also entries for the purchase of similar supplies for William Welchhans, Charlotte’s husband, and Elizabeth Dunlap, the girls’ aunt.

Many families in the neighborhood were engaged in weaving. An entry in Sterrett’s general store ledger shows Ann Hite Baer, the girls’ mother, trading many yards of tow linen for credit at the store. Tow linen was a plain fabric used for sacks and work smocks, and could have been woven without a draft.

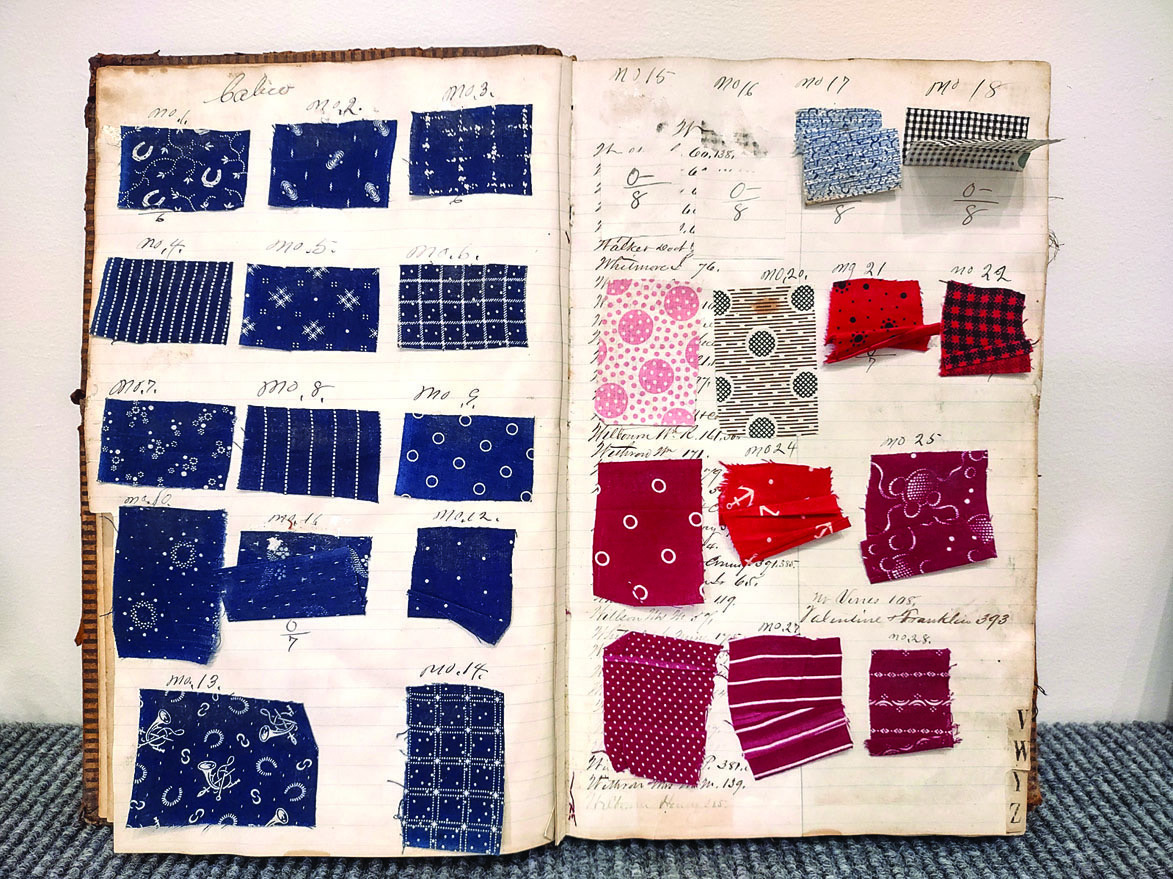

Ann Baer was using what she had left over from the family’s needs to supplement the family income. With her credit she bought silk handkerchiefs, shoes and glass knobs. Along with weaving supplies, neighbors were buying ready-made fabric such as Irish linen, muslin, calico, and cassinett, a wool twill used for men’s vests and coats.

A similar pattern of trading everyday, utilitarian fabric for store credit comes from the records of Moore and Dunlap’s store in Kerrs Creek.

Rockbridge County families in the 19th-century met their textile needs in many different ways, weaving both plain and fancy fabrics for themselves, as well as by buying or trading for them at the store. Between November 1841 and October 1842, local families brought in 368 yards of fabric for credit. The most commonly supplied fabrics were linsey (used for making petticoats and other garments) and jeans (most often used to make the namesake work pants; an early pair of the type is on display in the exhibit).

“I always feel connected to the past when at the loom, or spinning wheel, because we’re carrying on traditions that in one form or another span [long stretches of] history,” said weaver Khabira Wise. “Being able to reproduce historic drafts that are local, however, is extra-special in that it creates a direct link to the traditions and people of this area.”

The Fabric of History RHS Executive Director Eric Wilson stressed the exhibit’s joint appeals to the charms of craftwork, alongside the social networks that link and distinguish the most remote communities of Rockbridge County with wider regional, national traditions and developments.

“These archival discoveries and connections show how much family papers still have to add to this record, and broadly in local history,” he said.

“But the most innovative element here,” he continues, “is the crowdsourcing of new stakeholders – artists, archivists, multi-generational Rockbridge families still here – who bring their diverse contributions and questions. Frances’ energy and insight have been so powerful in threading this range of artistic and academic contributors into our fabric of history.”

In an RHS program later this fall, Richardson will give a slideshow presentation detailing her findings, and creative process. She’s also willing to arrange group tours and demonstrations beyond museum hours. To inquire about group tours and demonstrations beyond the museum’s weekend hours, contact [email protected].

THIS 1863 Rockbridge County map shows Panther Gap near the border of Bath County, just 4 miles above “Goshen Depot” (top is west). Several family homes and farmsteads featured in the exhibit are dotted through this community landscape. (Library of Congress)

THE PAGES of this 1860s daybook from Whipple’s general store in Brownsburg record a wide array of purchases and credits reflecting local exchanges in fabric consumption and production. Here, calico samples offer specific visual and tactile choices to customers. (loaned by Brownsburg Museum)

FRANCES RICHARDSON WOVE “The Vining Strawberry” based on an 1847 Baer weaving draft.

.jpg)