Jefferson’s ‘Public Trust’ Event At NBSP Marks 250th Anniversary Of Purchase

Editor’s note: The following article was written by Rockbridge Historical Society Executive Director Eric Wilson, also a member of the planning committee for the event described below.

After the Fourth of July fireworks, July 5 brings its own unique commemorations to Rockbridge, bridging our local community with the commonwealth and nation at large.

With special events organized at Natural Bridge throughout the day, Friday witnesses the historic anniversary – 250 years after that same date in 1774 – of Thomas Jefferson’s purchase of a royal land patent for the Natural Bridge from King George III.

Thanks to the joint sponsorship of several historic, environmental and civic organizations, the event invites visitors of all ages to enjoy the legacies of what the Bridge’s first private owner – and future governor and president – would come to describe not just as “the most sublime of nature’s works,” but as “a public trust.”

On the Fourth, Virginians will gather on their main streets, at backyard barbeques, or to hear the Declaration of Independence read on the steps of the State Capitol (its own architectural marvel, designed by Jefferson). But Friday’s program, “A Bridge to Revolution,” further centers attention on the Jeffersonian landmark in Rockbridge. The day’s themes highlight the twin pillars of natural resources and historic recognition, long anchored at Natural Bridge, now entrusted to the public as Virginia’s 37th state park.

As Natural Bridge State Park manager Jim Jones reflects, “The mission of Virginia State Parks is to preserve and protect cultural, historical and natural resources for future generations. As we approach our system’s 100th anniversary in 2036, there’s no better example of protecting a significant natural treasure than the Natural Bridge. I can’t think of a tribute more fitting to Thomas Jefferson’s vision for the Bridge than its status as a National Landmark, protected in perpetuity by the state of Virginia, and its Department of Conservation and Recreation.”

July 5 Ceremonies: “A Bridge to Revolution” At 11 a.m., a commemorative gathering under the Bridge’s 215-foot span will celebrate those legacies with addresses by state and local leaders, including park manager Jones, Matthew S. Wells, director of the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation; and Eric Wilson, executive director of the Rockbridge Historical Society.

The morning’s ceremonial remarks will be headlined by Terry L. Austin, delegate for the 37th House District in the General Assembly, and chair of the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission (VA250).

Collectively, their perspectives highlight the joint principles of environmental and historic conservation. They echo Jefferson’s resonant phrase that the Bridge stands as “the most sublime of Nature’s works ... so beautiful an arch, so elevated, so light, and springing as it were up to heaven, the rapture of the spectator is really indescribable!”

But they also emphasize how those reflections call us to consider the ideals and responsibilities of both stewardship and citizenship, today.

At noon, along Cedar Creek, Bizzee B’s BBQ will offer a holiday cookout lunch for sale. And throughout the day, visitors of all ages can enjoy the park’s trails and vistas, waterfalls and wildlife, as well as ranger demonstrations and educational displays.

Between 1 and 4 p.m., slideshow presentations in the visitor center will feature experts from Monticello, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and the Rockbridge Historical Society, who will variously speak to “Jefferson and Conservation,” “Natural Bridge in American Art,” and “Four Centuries of Tourism at Natural Bridge.”

As a special tribute, with Jefferson fronting the $2 bill, the park has reduced admission by that amount on the day.

Jefferson’s Growing Claims

Delegate Austin’s contributions signal his statewide leadership of the VA250 Commission, as well his representation of both Botetourt and Rockbridge counties, the two jurisdictions the Bridge has historically stood within, since their successive charters in 1770 and 1778.

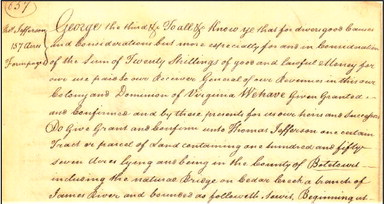

ABOVE, dated July 5, 1774, this royal land patent from King George III attests that, “for the Sum of Twenty Shillings of good and lawful Money… We Do Give Grant and Confirm unto Thomas Jefferson one certain Tract or parcel of Land containing one hundred and fifty seven Acres lying and being in the County of Botetourt, the natural Bridge on Cedar Creek, a branch of the James River.” (Library of Virginia). AT LEFT, although Jefferson bought the Bridge at age 31, this life sized 1801 portrait by Caleb Boyle shows him in older oversight, his cane aligned to highlight his beloved landmark, and Cedar Creek, set against an inviting horizon. (Kirby Collection of Historical Paintings, Lafayette College) BELOW, this section of wallpaper (made by the Parisian firm Zuber et Cie in 1834) uses the Natural Bridge as a backdrop to stage a fascinating if fanciful vision of cosmopolitan, multiracial tourism, and indigenous ritual or performance. Jefferson wrote to many European friends inviting them to visit the Bridge, whose portal often stood as a symbol of Americans’ rapid westward expansion. (Virginia Museum of History and Culture)

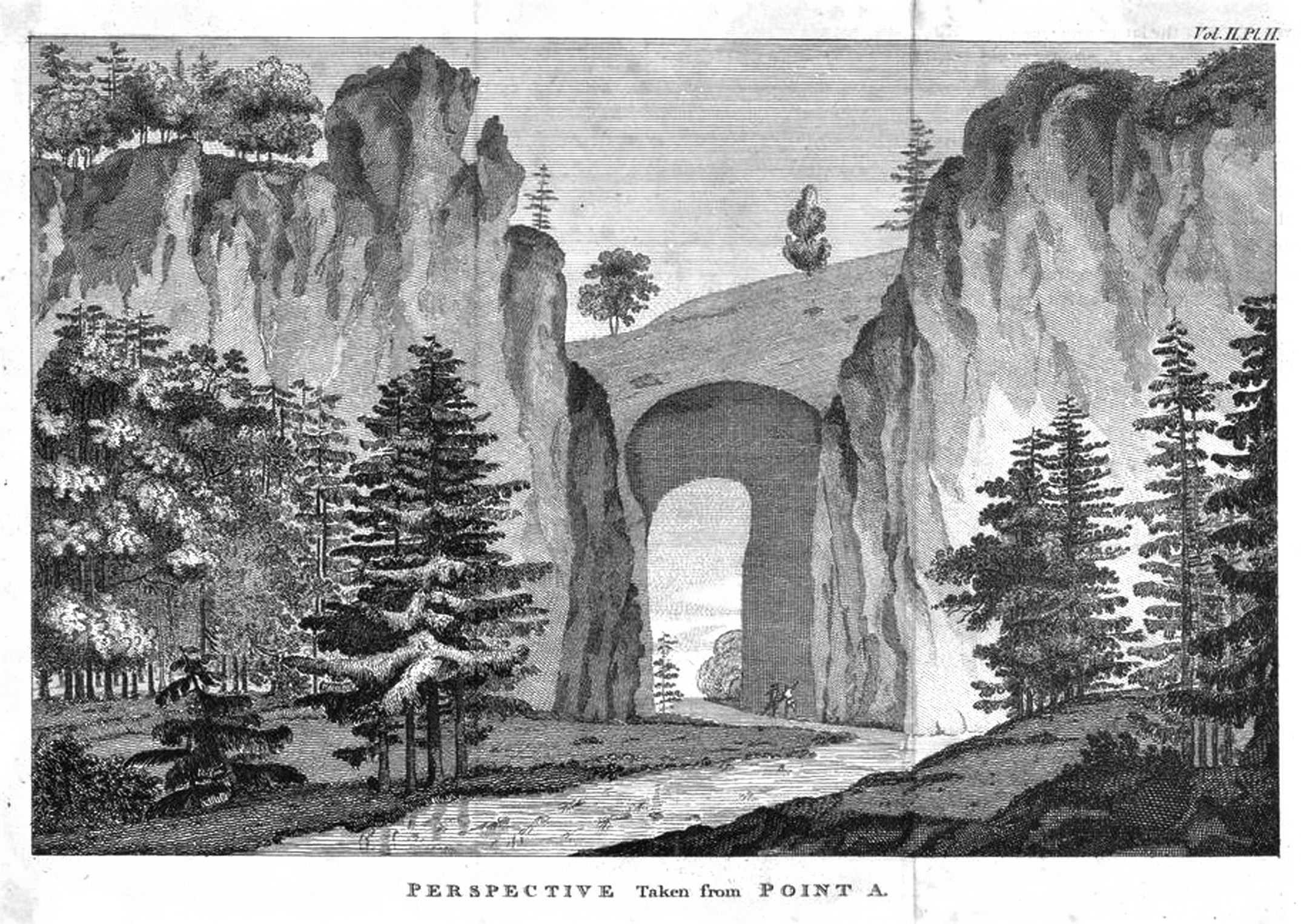

THE MARQUIS DE CHASTELLUX served as a general in the French Army at Yorktown. Soon after the revolutionary victory, he visited Monticello, where Jefferson encouraged him to see Natural Bridge, having bought it just seven years earlier. Chastellux would chronicle his “Travels in North America 1780, 1781, and 1782,” including this engraving, after Baron de Turpin, the first known published image of the arch. (Virginia Museum of Fine Art)

As colonial Virginia expanded through the heart of the 18th century, royal claims on those lands west of the Blue Ridge encouraged enterprising settlers to cultivate its fields and forests, and to provide security in uncertain terrain.

From the Piedmont into the Valley, those inroads extended even further into the traditional homelands of the Monacan empire. Their ancestral generations had lived in the region for thousands of years, their descendants then in the midst of growing “frontier conflicts” in the era between various European and indigenous nations.

In that crucible, and with those incentives, Jefferson secured his purchase of Natural Bridge and 157 surrounding acres of Botetourt County land for just 20 shillings. Monticello scholars have calculated his total costs for surveying and acquiring the Bridge as the equivalent of $160 today. Jefferson’s contract with King George III and Governor Dunmore was inscribed into the royal patent book on July 5, 1774.

That date holds an uncanny echo, near exactly two years before the July 4, 1776, publication of the Declaration of Independence, the most famous and lasting work from Jefferson’s hand. But in 1774, he couldn’t have yet projected his role in that enterprise.

At the time, he was still a young Virginia lawyer and plantation owner. He’d just recently begun designing Monticello, and had only been married two years. In 1773, the year before he purchased the Bridge, he’d inherited 1,100 acres through his father-in law’s will, as well as the rights to another 135 enslaved people. In all attendant reckonings of land, finance and human property, Jefferson’s investments in Natural Bridge real estate were small in both scale and cost. In time, he would come to own over 10,000 acres of Virginia lands. But his stakes in the Bridge still loomed large in mind: frequently writing of it to friends in Lexington, and internationally abroad.

During the same summer when he bought the Bridge, Jefferson was also drafting a document that was ambitiously titled, “A Summary View of the Rights of British America.” That assertion of colonial freedoms proved too radical, in 1774, to include him in Virginia’s delegation to the first Continental Congress, yet foundational for his later leadership and selection to author the Declaration.

These financial and political contexts are important, not just to understand Jefferson’s own standing and perspectives, but also the property-owning experiences of many Virginians at this time. The year 1774 does not only herald the growing ferment we can retroactively see – at the cusp of a revolutionary break, in state and national governance – but a growing affirmation of American property rights, and economic self-determination.

Four years later, in 1778, the new political jurisdiction of Rockbridge County would be established, not by the Crown, but by a newly empowered Virginia legislature. It was chartered as a wartime measure to anchor military security, and expand a growing chain of county courthouses. And notably, it was named for Jefferson’s privately owned natural landmark, not a British aristocrat.

Now recognized as personal property, Jefferson’s acquisition signals another shift away from the generational stewardship of Monacan peoples, and from royally granted patents. For the first time, Natural Bridge was marked by an individually owned deed, painstakingly marked by local streambeds, tree clusters, and other fence corners. After the Bridge was sold in 1833 (to pay down the debt on Jefferson’s estate), the chain of private ownership would continue: changing hands for nearly two centuries, before its most recent transition into the state park that advances Jefferson’s vision of “a public trust,”

Private Purchase, Public Trust

Although he lived nearly 100 miles away, Jefferson didn’t buy the Bridge blind. George Washington was said to have surveyed it in 1750, though the written record is not clear. The influential 1753 map plotted by his father, Peter Jefferson, had charted the region two decades before, if still spare in the noted settlements and topography in these parts (with no mention or illustration of the Bridge, just yet).

But Thomas Jefferson first visited the Bridge himself when he was 24, on Aug. 23, 1767. Characteristically, for his scientific cast of mind, he took careful measurements of the structure: drawing its geometric dimensions onto the flyleaf of his notebook, with comments that he would more fully draft into his 1785 “Notes on the State of Virginia.” His lyrical account of the Bridge in that volume will be on display during the July 5 event, along with a framed copy of his deed of purchase.

The young Jefferson would still have been among the first generation of European settlers to have recorded visits there. Monacan traditions held this place sacred for millennia, however, with oral histories addressing the iconic span as “Mohomony,” meaning “The Bridge of G od.” T heir l ongstanding understandings of land tenure, resource, stewardship, and collective responsibility would differ distinctly from the late-colonial land patents of the Beverly and Borden grants, from Jefferson’s own, and from the grants of the post-revolutionary Republic, as variously recorded and contested

in deeds.

But most distinctively here, over 40 years after those earliest encounters, Jefferson wrote a letter articulating a vision that still resonates today. On March 15, 1815, Jefferson addressed his friend and Lexington lawyer William Caruthers, who handled some of Jefferson’s local business affairs. In its conclusion, he writes,“I have no idea of selling the land. I view it in some degree as a public trust, and would on no consideration permit the bridge to be injured, defaced or masked from the public view.”

To be fair, Jefferson had in fact attempted to sell the Bridge, when trying to right his postpresidency finances in 1809. Writing to William Jenkins of Rockbridge after an earlier conversation “on the sale of my lands at natural bridge,” Jefferson surprisingly notes that “on reflection, I find that it is a dead capital in my hands, that in other hands, it may be useful to the owner and the public, I am therefore willing to sell it, with respect to price.”

And yet, even in that moment of financial need, Jefferson sounded his familiar chord: his vision of the Bridge being “useful to … the public.” And despite all the other sales of property and people throughout his life, Jefferson never did sell the Bridge, keeping possession for 52 years, until his death on July 4, 1826.

Exploring History, Conservation, Art, Tourism

Building on generations of tourism, and governmental commitments to conservation and inclusive access, Jefferson’s “public” vision has now found various points of echo in our state park system.

To further explore this range of themes, the day’s events conclude with presentations by Monticello’s director of historic interpretation, Brandon Dillard; VMFA Curator Christopher Oliver; and RHS Executive Director Eric Wilson. Their slideshow talks (starting at 1, 2, 3 p.m., respectively) will variously illustrate perspectives spanning the two centuries Jefferson owned and wrote about “The Rock Bridge” and Virginia; surveying three centuries of artistic drawings, paintings and photographs; and four centuries of tourism, connecting Rockbridge residents and visitors in a wide sweep of leisure, and labor.

To close, an especially captivating account of visiting the Bridge during Jefferson’s era: written in 1817 by his 18-yearold granddaughter, Cornelia Randolph, as they traveled there together.

Her romanticized account echoes Jefferson’s own fantasias on the sublime: “It is impossible to judge of the height from the top, but when you go down & see how large objects are which you thought quite small you are astonish’d … The scene was beyond anything you can imagine possibly.”

But she also notes the social realities of managing a rugged if attractive landscape, supported by the attentive care of a guide: “We should have been oblig’d to come away with scarcely an idea of the bridge if it had not been for the exertions of Patrick Henry who worked for nearly an hour to contrive us a way by which we might get along.”

Significantly, Henry was not the Virginia statesman of the same name who spoke of liberty and death in 1775, but a formerly enslaved free man of color whom Jefferson had hired to be caretaker of his lands, to pay local taxes, and to guide visitors.

Again, questions of public access, of public trust may differ from our own expectations today. But it does seem fitting to note that new markers at the state park invite us to think of Henry’s labors, of his welcome, as the model of the Bridge’s first park ranger.

For a wider sweep of 18th-21st century encounters and illustrations, see the virtual rendering of RHS’ 2014 exhibit, “Images of the Rock Bridge” at tinyurl. com/RHS-Natural-Bridge.

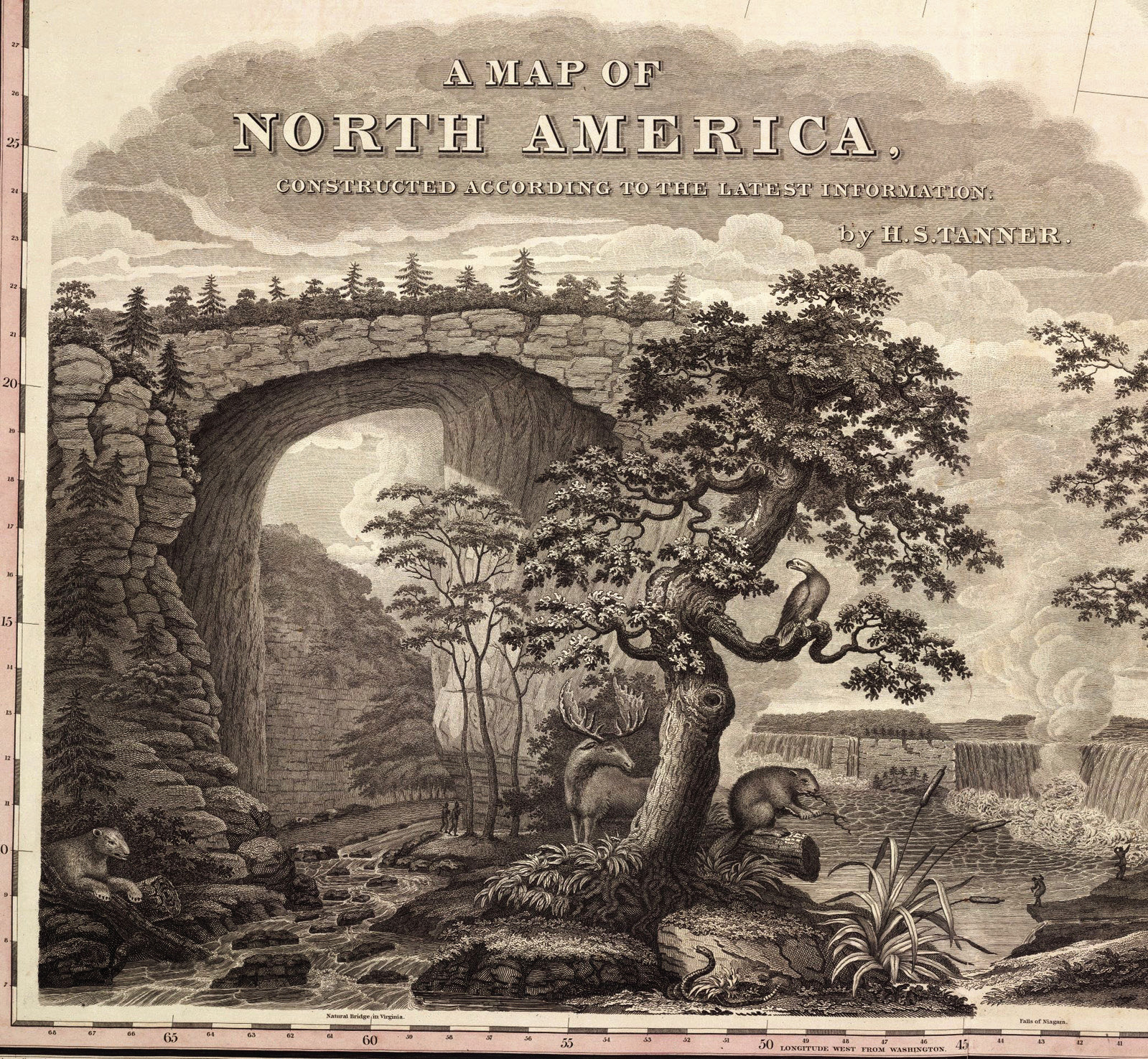

THIS CARTOUCHE sits in the corner of Henry Schenck Tanner’s large 1822 “Map of North America,” published just four years before Jefferson’s death, and two decades after he’d commissioned Lewis & Clark’s expedition to the Pacific. The inset image features the era’s common coupling of the Natural Bridge and Niagara Falls. A pair of human figures is barely visible under each, here, to offset the naturally dynamic topography, and zoology. (Beinecke Rare Book Library, Yale University)

.jpg)