Vietnam Veteran Reunites With His Restored Plane, Crew Chief

Editor’s note: Retired Air Force Lt. Col. Bob “Hoppy” Hopkins of Lexington, who flew a F-100 fighter plane during the Vietnam War, was invited to a dedication ceremony at a museum in Ohio early this fall that was very special to him. He has written about that experience for us, and we’ll let him tell you all about it.

This fall, a very unusual event took place at the Military Aviation Preservation Society’s (MAPS) Museum in Canton, Ohio.

It was the dedication of artifacts and memorabilia of the F-100 Super Sabre fighter plane. The F-100 was the first operational fighter that could go supersonic in level flight. It also flew 360,283 combat missions in Vietnam, more than any other jet aircraft in that war.

During that war I had the honor to fly the F-100, specifically plane serial number 56-3081, (081) that is on permanent display at the museum.

It was (and still is) customary to assign each plane to a specific pilot and maintenance crew chief who is responsible for that plane’s combat readiness each time the plane flies. The crew chief in 1968 was Leo Lamoureux, a 20-yearold sergeant with a Boston accent who greeted me with a salute when I arrived at the plane, assisted with the aircraft walk-around pre-flight checks, helped me strap in the ejection seat and sent me off with another salute and thumbs up. Both Leo and I were at the dedication event.

The Survivor

On June 19, 1957 (my birthday), the plane was first assigned to active service in the USAF. Ten years later it was assigned to Bien Hoa Air Base in South Vietnam where I was stationed. In 1968 I was assigned to the plane and my name was painted just below the canopy. It read, “Pilot Capt. Hoppy Hopkins.”

I did not fly the plane every time it flew but I flew it often. It was in Vietnam for three years, flying on average once a day to accumulate about 1,000 combat missions. One time I brought it home with eight bullet holes under the cockpit and through the wing. Another pilot flew it home with the canopy shot off.

The closest call I had was when I got too low and flew through tree tops in a rubber plantation. When I landed, both wing tip lights were gone and there were pieces of rubber tree instead.

The plane survived the war and was sent back to the States in 1971 where it flew with the Air National Guard until 1979.

Then it was retired and sent to the desert “boneyard” near Tucson, Ariz. It sat in the sun for 10 years until in 1989 it was modified into a drone and sent to a base in Florida as an airborne target for more modern fighters over the Gulf of Mexico.

It survived in this role for a half dozen or more sorties but was eventually hit with a Sidewinder heat-seeking missile. The missile went through the left wing but did not explode, just left a hole.

Deemed too expensive to repair, the plane then went to an outdoor airplane museum in Clearwater, Fla., where it sat outside until that museum closed in 1999. It was then moved to an airplane “graveyard” exposed to the elements until rescued by the MAPS Museum in 2004. It was then transported to Canton, Ohio, where it was totally restored over the next seven years to look exactly as it looked during the Vietnam War.

DURING THE DEDICATION event for the restored plane in September, Bob Hopkins and his crew chief during the Vietnam War, retired Sgt. Leo Lamoureux, were able to reenact the 1968 photo seen below.

The Dedication

On Sept. 14 of this year, completely restored to its wartime experience, “081” was honored by a dedication ceremony attended by former F-100 pilots, crew chiefs, restoration artists and families.

There, parked in front of a giant American flag she sat with a ladder on one side and a set of stairs on the other so people could climb up and sit in the cockpit as I did for about five minutes, looking for the first time in 56 years at those same instruments, switches, throttle and control stick with the trigger that I used so many times while in Vietnam.

Nothing had changed except me.

The cockpit felt the same but seemed smaller. Memories came flooding back and a warm feeling of being back with an old friend came over me.

I felt sorry for the plane that had flown so gallantly during the war and then was subjected to so many abuses and was almost shot down as a drone to a final resting place on the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico, never to be seen again.

Yet here I was sitting in the cockpit of the plane I love ... the plane that brought me home safely so many times.

Another very special event happened at this dedication event. My crew chief, Leo Lamoureux was also there.

We had agreed before we met to wear uniforms as close as possible to the ones we wore in Vietnam. I had a newer flight suit that I last wore in 1982 and Leo found a Vietnam-era uniform so when we met at the plane we tried to look the part.

Leo had not seen his plane in 56 years and when he saw it, tears welled up in his eyes and he gently ran his fingers down the side ... touching the same airplane that he had worked so hard on in Vietnam. His name was repainted just below the right edge of the canopy.

He and I hugged and reminisced and laughed and got watery eyes together. It was very special for us. When we parted the next day he said to me, “I love you.”

I felt the same way but said nothing. I wish now that I had.

The Exhibit

The MAPS Museum dedicated a large area where F-100 memorabilia and artifacts would be displayed and cared for in perpetuity.

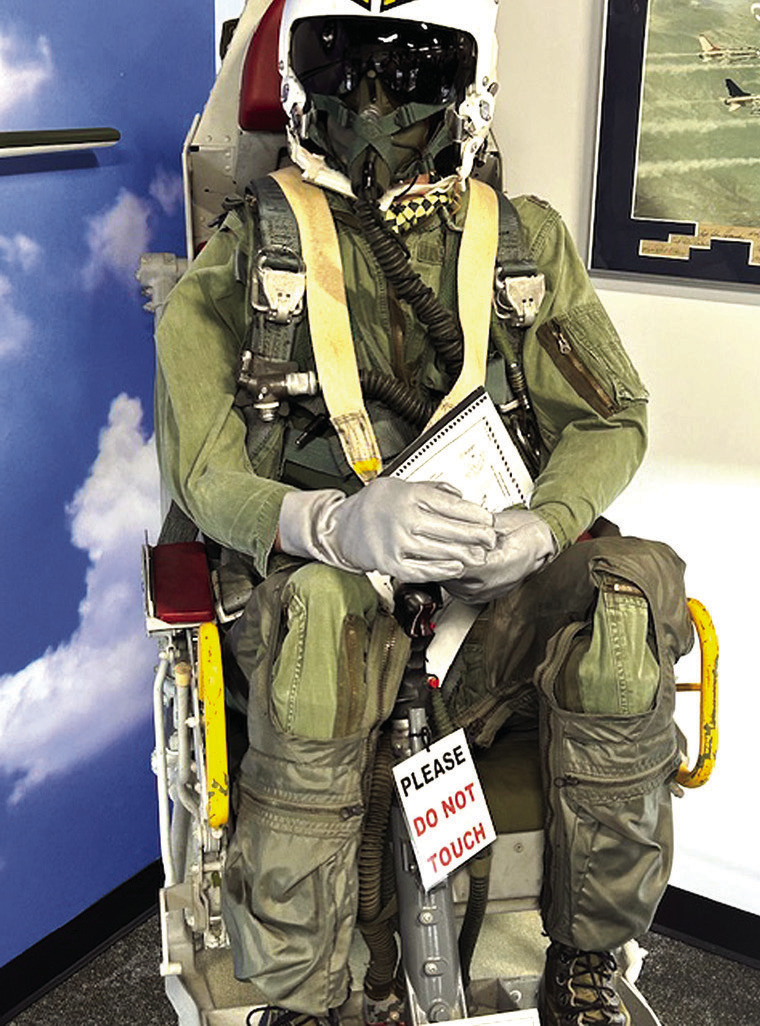

There on display is the Medal of Honor, earned by Col. George Day (F-100 pilot and POW), a mannequin dressed in actual Vietnam flight gear sitting in an ejection seat, the actual vertical tail of a USAF Thunderbird F-100, an air refueling probe and drogue hooked up, a beautiful “toasting cabinet” made by Rockbridge expert cabinet maker Talmadge Fix, the front windscreen of an F-100 with a bullet hole (luckily it did not penetrate), the complete F-100 art collection of world renown aviation artist Keith Ferris, a 3D model F-100 with a 16 foot- wingspan coming out of a wall with blue sky and clouds in the background plus hundreds of other objects pertaining to the pilots and ground crews.

If any readers of this story ever get a chance to go to Canton, I would encourage them to stop by and spend some at the museum, and tell them “Hoppy” sent you.

A MANNAQUIN dressed in actual Vietnam-era flight gear sitting in an ejection seat is also among the exhibits at the MAPS Museum.

THIS SHOWCASE at the MAPS Museum features the Medal of Honor received by F-100 pilot/POW Col. Bud Day.

THIS F-100 pilots’ “Toasting Cabinet” houses glasses used by surviving Super Sabre veterans to toast each other and their fellow pilots who have died. The cabinet was built by the late Rockbridge County woodworking craftsman Talmadge Fix at the request of Bob Hopkins.

.jpg)