Cedar Grove Once Thrived As ‘The Highest Point of Navigation’ On Maury

Cedar Grove was once a bustling community where the North (Maury) River intersected the Middlebrook-Brownsburg Turnpike (Va. 252). Flat-bottomed boats, known as bateaux, transported iron from nearby forges, whiskey, flour, and agricultural products to the James River, making it one of the most important commercial sites in the county. Over time its economic significance diminished, and today little trace of it can be found. To honor the people who lived and worked in the Cedar Grove area, a historical marker from the Virginia Department of Historic Resources is being erected at the site and a ceremony to unveil the marker will be held on Sunday. The marker was proposed and sponsored by David and Diana Hopkins who live nearby. In this article, David Hopkins tells the story of Cedar Grove, with acknowledgement of editorial and historical assistance from Larry Spurgeon.

“As pretty a place as I had ever seen … The hill rising abruptly in back of our house was covered in cedars. The river lay in front with greensward lying between the yards and the river.”

With these words in 1833, Mary Horn Anderson, the young bride of Robert Blaine Anderson, described the setting that inspired the name for the village where her family owned a mercantile. The Horns and the Andersons were among the many families connected to Cedar Grove and the surrounding area.

Cedar Grove was located on two Borden Grant tracts. In 1757, James Anderson received 200 acres on the North Branch of the James River, bordered on the east by Back Creek. The second grant of 210 acres, deeded to David Quinn in 1768, was bordered on the west by the creek. The Anderson family continued to own property at Cedar Grove until 1849, though parcels were sold, including the tract near Back Creek and the North River where the grist mill was located. Built along Back Creek, likely by Isaac and William Caruthers, the mill was known as Cedar Grove Mills by 1819, and became the most enduring structure in the village. The dependable spring creek powered the mill; it remained in operation for nearly 100 years.

The iron industry west of the Blue Ridge Mountains was well established before 1800, but the ore and charcoal to maintain furnaces and forges were remotely located in the western flank of the Blue Ridge and west of Little North Mountain. At least 21 forges, foundries, and furnaces operated in the county near the North and South rivers.

Lacking suitable roads, the James River watershed became a prime means of moving goods to market. The North fork of the James, (the North River, later the Maury), has difficult rapids below Goshen pass, but downriver from Cedar Grove the character of the river allowed for water transportation.

By 1801 Cedar Grove was recognized as the “head of navigation” on the North River, an embarkation point for goods to be transported downriver to Lexington, Lynchburg and Richmond. It served as a staging area for river transport, and as a marketplace for local farmers and merchants. Located at the intersection of the Middlebrook and Brownsburg Turnpike and the Beverly Manor Turnpike to Alum Springs and

, page B2 Goshen, and with a connection to the North River Road to Lexington, Cedar Grove was a center of economic activity.

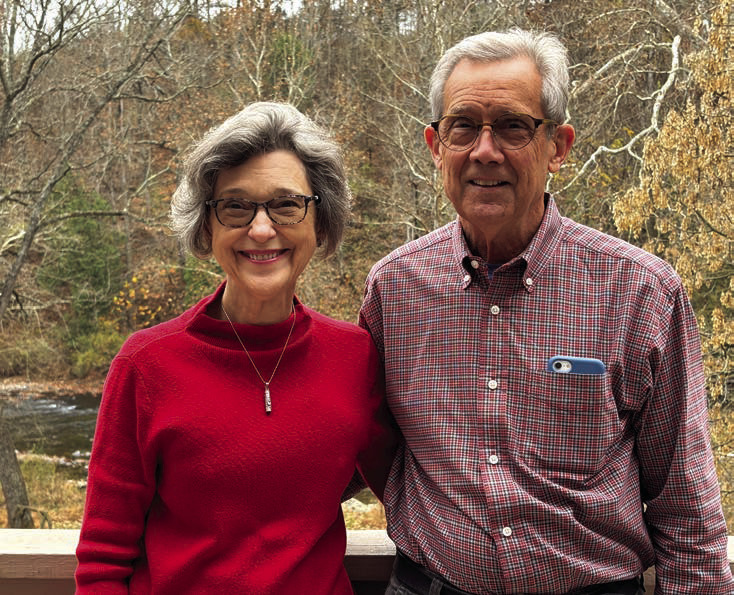

DIANA and David Hopkins (at far right) own the property along the Maury River where the Cedar Grove community once stood. Among the few reminders of the community is this millstone at the site of Cedar Grove Mill. Below is the Maury River looking east near its confluence with Cedar Grove Creek where the grist mill was. (photos by Aileen Spurgeon and David and Diana Hopkins)

THESE ORIGINAL stone blocks were for the road that ran from Cedar Grove west to Rockbridge Baths and on to Goshen. An 1860 map shows the road and it is assumed the road had been there many years before then. (photo by Larry Spurgeon)

One of several boatyards in Rockbridge County flourished at Cedar Grove. The bateaux and barges built there made a one-way trip downriver – it was extremely difficult to navigate upriver without the features of a canal. The boats were sold or disassembled for lumber at the downriver locations.

Don Stockley built barges at Cedar Grove, some up to 90 feet long, poled by a crew of four and able to carry nine tons of freight to Lynchburg and Richmond. An 1830 announcement in the Lexington Intelligencer, promoting the opening of a mercantile at Cedar Grove, stated, “All kinds of produce will be received on storage and forwarded to Lynchburg or Richmond by respectable boatmen.” The boatmen were typically enslaved men who knew the river and its hazards. Freight costs were advertised at 8 cents per 100 pounds.

As the village grew in economic importance it became known as Cedar Grove Mills and was, by some accounts, the “metropolis of Rockbridge.” The Cedar Grove Mills Post Office opened in 1832; William Withrow, the co-owner with his brother-in-law Henry Boswell Jones of a mercantile at Cedar Grove, was the postmaster. In 1835 the village was noted in the “Gazetteer of Virginia” as a Rockbridge County location with two mercantiles and a manufacturing flour mill. Robert Anderson was co-owner of the Anderson Youel store in the village that was open for over a decade. Robert died in 1853 of consumption (tuberculosis) leaving his wife Mary a widow with eight children. With her family nearby, Mary would live to 87 and is buried at Bethesda Presbyterian Church in Rockbridge Baths next to her husband.

Isaac Caruthers sold the mill to Thomas Orbison in 1819 for $3,000. Orbison sold it two years later to William McKee, who was forced by a lawsuit in 1829 to sell. John Randolph purchased the mill along with 110 acres, and it became known as Randolph’s Mill. By this time, it was a “merchant mill,” with the miller buying grain and selling flour at market. Randolph’s Mill advertised “superfine flour” and assured shipments to Lynchburg and Richmond.

Warehouses were built to store bar iron from the forges, flour from the mills, liquor, hemp and agricultural goods. By the 1850s Cedar Grove Mills had two mercantiles selling goods from Philadelphia and Richmond, a tailor shop owned by James Webb, two blacksmith shops, a wagon maker’s shop, a cooper’s shop, a boatyard, a sawmill, a grist mill, and several homes. In January 1852, over 60 citizens petitioned the General Assembly to establish a voting precinct at Cedar Grove Mills.

Andy’s Story

Black people, most of them enslaved, no doubt performed much of the physical labor at Cedar Grove. Though little is known about them, an exception is a free man of color named Andy, formerly enslaved by John Walker, who died in 1816.

Walker’s will provided that Andy was to be emancipated at age 35, and until then, Joseph Walker was to own him and teach him to read. Andy turned 35 in 1835, and registered as a “Free Negro” with the Rockbridge County court clerk. The court approved the registration, but Virginia law provided that emancipated people had to leave the state within one year, unless a petition to remain was successful.

Andy placed an ad in the Lexington Gazette on Jan. 1, 1836, stating his intention to petition the General Assembly for “permission to remain in this Commonwealth,” giving his residence as “Cedar Grove.”

Perhaps he worked in the mill or in loading the bateaux. In his petition, filed on Jan. 14, 1836, Andy Walker stated that he was born and raised in Rockbridge, and that “almost all his friends and relations reside there, that he has a wife and children who are slaves and who are the property of Robert Hutcheson, Esq.”

Thirty-six white men, including Hutcheson and several members of the Walker family, signed a statement that Andy was a “man of excellent character and we believe that no evil consequences would result from his being permitted to remain in this commonwealth, and we are desirous that he should so be permitted.”

On March 23, 1836, the Virginia Assembly enacted a law that permitted Andy to remain in Virginia for five years, “but no longer,” and authorized the Rockbridge court to order Andy to leave if it found cause.

Robert Hutcheson died in 1842, and in his will mentioned an enslaved man named Andy, suggesting the possibility that Andy chose to be re-enslaved rather than leave his wife and children.

A Slow Decline

James Randolph deeded the mill and property to his son James in 1850. James married Mary Trevey the next year. As owner of the mill and a new mercantile he built warehouses, a fine house, and prospered as the community grew.

In 1856 however, James Randolph ran an ad in the Richmond Inquirer for the public sale of his Cedar Grove Mills estate. The property consisted of 185 acres divided by Back Creek, with a four-story merchant mill, a warehouse on the bank of the river, a large storehouse at the junction of the two turnpikes, and a commodious frame dwelling house. The last line read: “Wealthy and intelligent neighborhood, one of the best stands in the Valley for a mill and a store.” Randolph, though only 33, with a wife and two daughters, cited failing health and retirement.

Henry Horn bought the mill property from Randolph in 1859 along with 160 acres for $12,000. James Randolph died in 1860, on the eve of the Civil War.

Over time Cedar Grove’s commercial significance began to wane. The river was unreliable due to low water and prone to flooding. Court documents from as early as 1830 record petitions which described the North River as “altogether useless” to carry goods for months at a time. At an 1839 court hearing the ironmaster of Gibraltar Forge, located about a mile upriver from Cedar Grove, complained that the bateaux ran only six months out of the year.

Attempts to improve the navigability of the North River included wing dams and using explosives to form channels in the bedrock and ledges. Even at favorable river conditions the journey was perilous, and freight was often lost overboard. The flood of 1847 swept away a warehouse full of corn at Cedar Grove and inundated Gibraltar Forge and the Lebanon Valley forge near Rockbridge Baths.

By the 1850s the local natural resources supporting the iron industry were depleted; the furnaces and forges along the North and South River were closing. The North River canal had reached Lexington in 1850, and by 1860 the North River Road extended to Cedar Grove and connected to the Brownsburg Turnpike. River transport was declining in favor of more reliable road and canal transportation.

Without an iron and riverbased economy, local business activity shifted from Cedar Grove to Rockbridge Baths, and freight moved to the more reliable North River canal in Lexington.

Cedar Grove Mills remained a market location through the 1870s with a few stores, a blacksmith, and the mill. The post office closed in 1873. By the 1880s, the commercial activity at Cedar Grove had all but disappeared. The mill continued to operate but had several owners after the village vanished. A bankruptcy court order required A. A. Humphries to sell the mill property in 1874. It was owned briefly by Frank Schultz, then A. A. Nicely and then James Dixon. The Flumen Post Office was established at the Cedar Grove location in September 1891 and a new voting precinct with that name was formed. James Buchanan was the Flumen postmaster and miller.

In 1904, James G. Dixon ran an ad in the Lexington Gazette to sell the mill property, “consisting of a four-story mill building,” with a capacity of 5,000 bushels of grain. The mill remained in operation until at least 1916, when the dwelling house was destroyed by fire. Fortunately, the miller, E. M. Smith, escaped with most of his household goods.

Only Rubble Remains

None of the buildings from that period remain. The river and time have left only the rubble of a mill foundation and the rock walls which supported the road along the river and creek.

The mill gave its name to the village, and the creek now carries the name “Cedar Grove Creek.” It is still a pretty place, nested along the scenic Maury River with cedars on the hillside and a greensward lying along the riverfront. When the water is favorable, the river gives sport to kayaks, canoes, and fishing, instead of carrying bateaux.

No longer on maps or in gazetteers, Cedar Grove has been recognized by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources for its importance to the development of the iron industry in Rockbridge County and the economic growth of the county. A historical highway marker will be erected at the location of Cedar Grove Mills on Maury River Road, Virginia Highway 39, just west of the intersection of the Brownsburg Turnpike. The citation on the marker reads:

Cedar Grove “Here at the head of smallboat navigation on the Maury (North) River, Cedar Grove had become a transportation hub and market center by the 1830s. The community grew along with the region’s iron industry, which played an important role in Virginia’s economic development. When water conditions permitted, enslaved and free boatmen used bateaux to transport iron from local furnaces and forges, as well as flour and other goods, to Lynchburg and Richmond. Served by two toll roads, Cedar Grove featured mercantile stores, a gristmill, warehouses, and a post office. The decline of the local iron industry later in the 1800s and disuse of the river for transportation led to the town’s abandonment.”

.jpg)