Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part series about the four Henry brothers of Rockbridge County. Born into slavery in eastern Virginia in the late 18th century, they were emancipated and built new lives in Rockbridge County, becoming exemplars of resilience and perseverance. The author is Larry Spurgeon, president of the Rockbridge Historical Society.

Nine of 10 Black people in Rockbridge County in the early 19th century were enslaved. Few traces of their very existence survive in historical records. Free people of color, by contrast, appeared in censuses, tax records, and in some cases, deed records. We know more about the biographical details, but what was life like for them?

An N-G Series

Free status for a Black person was very different from the rights and privileges of white citizens. Free people of color could own property and legally marry – unlike enslaved people – but were subjected to the same prejudices and stereotypes. White citizens lived in constant fear that free people, especially if educated, would instigate rebellion among the enslaved population.

Virginia law imposed severe restrictions on them. An 1806 law mandated that emancipated people leave the state within one year unless a court granted a petition to remain, deterring slaveowners from emancipation, the very intent of the law. Another statute required registration with the county every five years, and if they failed to produce their papers on demand they could be jailed. A second arrest could result in a punishment “with stripes.”

Despite these many obstacles, the Henry brothers led extraordinary lives. Patrick Henry was the first caretaker of the Natural Bridge, through an agreement with its owner, Thomas Jefferson. John V. Henry was employed by Washington College, owned a house in downtown Lexington, and emigrated with his family to Liberia. Duncan Henry and Williamson Henry were subjected to legal measures to re-enslave them, and fought back, suing powerful men in Rockbridge County, securing rare legal victories for men of color. More than two decades later Williamson Henry moved his family to Ohio, and some of his descendants can be traced to today.

Born Into Slavery

The Henry brothers and their mother Lavinia were among three dozen enslaved people owned by Martin Tapscott at his 500-acre estate in Westmoreland County, the birthplace of both George Washington and Robert E.

Lee.

It was located a few miles from Nominy Hall, the home of Robert Carter III, a member of one of the “first families of Virginia.”

His grandfather, Robert “King” Carter, was a royal governor, and one of his cousins was Anne Carter Lee, Robert E. Lee’s mother.

In 1791, Carter began the gradual process of emancipating more than 500 enslaved people, the largest manumission by an individual in the United States.

Tapscott made an emancipation deed in 1794 for Lavinia, for her “faithful services, together with other conscientious motives.” Some historians presume Lavinia was his “mistress,” and that Tapscott fathered her sons, though he made no attempt to emancipate her children at the time.

Tapscott wrote that if “through old age or infirmity” Lavinia would become “incapable of subsistence,” she would be furnished with “a competent and comfortable subsistence out of the profits of my estate.” For unknown reasons, the deed was not recorded until 1805, after Tapscott’s death, so Lavinia remained in slavery for at least another decade.

Tapscott died in 1804 and by his will gave his son Henry Brereton Tapscott the entire estate. Henry Tapscott would be the owner of the enslaved people – except as otherwise specified – until his death, at which time they would be emancipated. Since Henry was about 17, that could be a very long time. An exception was that Lavinia would be “emancipated and sett free agreeable to an inst r ument of writing in her possession given by me bearing date the 28th day of April 1794.” Henry Tapscott was not of legal age at his father’s death, so the estate’s executor managed the real and personal property, including the enslaved people.

Tapscott expressed his intent that “four or five of my negro boys (as near the age of my son Henry Brereton Tapscott as can be fixed) be bound to some profitable trade until they are twenty one years of age.” If Henry died without heirs, “all the young negroes that the law cannot emancipate owing to their minority shall be bound to some profitable trade.”

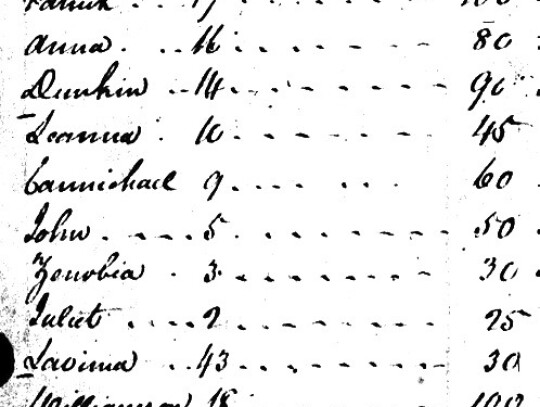

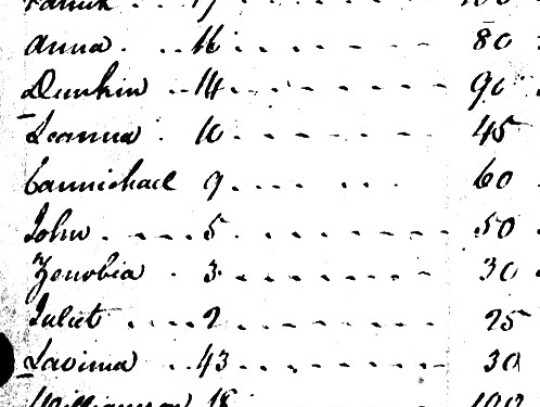

The 1804 inventory of Tapscott’s estate listed 35 enslaved people including Lavinia, 45, Williamson, 18, Patrick, 17, Dunkin, 14, and John, 5. Based on legal papers filed later, she also had a son named Aleck (Alexander), 20, and at least one daughter, name unknown.

Martin Tapscott had expressed his “will and desire that my son Henry Brereton Tapscott be kept at school in order to obtain a good English education.” Henry was taken to Lexington in 1805 to enroll at Washington Academy, and was listed as a student for the 1806-07 academic year. He died not long after and all of the enslaved people should have been freed, but that was not to be.

Patrick Henry (c.1787-1829)

Patrick Henry was purchased for $300 in 1806 from Martin Tapscott’s estate by his brother, John Tapscott of Westmoreland County.

Five years later John Tapscott made an emancipation deed for Patrick, conceding that Martin intended to emancipate him, but was prevented from doing so by his sudden death. John promised to emancipate Patrick when he paid back the $300. The deed explained that “Patrick by his own exertions and from the liberality of others hath been able to make up the said sum of Three hundred Dollars which he hath paid to the said John S. Tapscott.”

Finally, in 1811, Patrick Henry was legally free. He first appeared in Rockbridge County personal property tax records two years later. On Dec. 2, 1816, he recorded an emancipation deed, explaining that the previous year he had purchased from Benjamin Darst a “female slave named Louisa, and since known by the name of Louisa Henry.”

His sentiments are poignant: “[n]ow, for and in consideration of her extraordinary and meritorious zeal in the prosecution of my interest, her constant probity and exemplary deportment subsequent to her being recognized as my wife, together with divers other good and substantial reasons, I have this day in open court, in the county aforesaid by this my public deed of manumission determined to enfranchise, set free, and admit her to a participation in all and every privilege advantage and immunity that free persons of colour are capacitated, enabled, or permitted to enjoy in conformity with the laws and provisions of this Commonwealth in such cases made and provided. And by these presents I do hereby emancipate, set free, and manumit and disenthrall, the said Louisa alias Louisa Henry from the shackles of slavery and bondage forever.”

Thomas Jefferson purchased the Natural Bridge and 157 acres in the 1780s. Lexington resident William Caruthers managed Jefferson’s business affairs in Rockbridge, and in 1817 wrote Jefferson that “Patrick Henry a free man of Colour requested me to write you that he will rent what land is cultivatable on the Bridge Tract – which is perhaps 10 acres all of which [he] is to clear off and enclose and for which he is willing to pay a fair value. Patrick is a man of good behaviour and as the neighbors are destroying your timber verry much it might not be amiss to authorize him to take care of it in order to which it might be well to have the lines run by the surveyor of the county.”

Jefferson responded to Caruthers that “I readily consent that Patrick Henry, the freeman of colour, whom you recommend, should live on my land at the Natural Bridge, and cultivate the cultivatable lands on it, on the sole conditions of paying the taxes annually as they arise, and of preventing trespasses.”

Caruthers died the same day Jefferson wrote the letter, so Andrew Alexander of Lexington wrote Jefferson that Patrick Henry agreed to the arrangement.

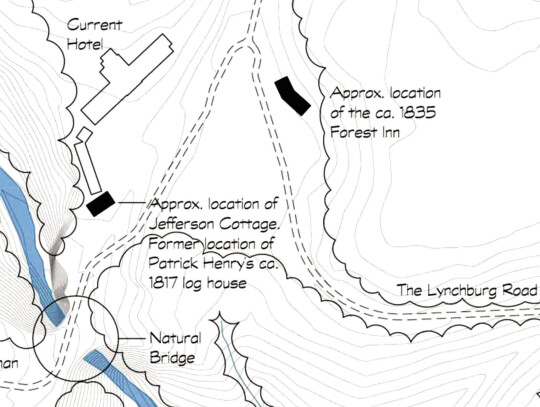

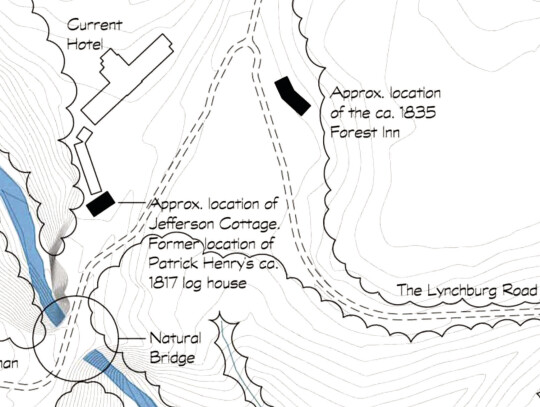

Patrick Henry built a tworoom log cabin on a stone foundation 150 yards from the arch, on the site of a later structure known as Jefferson Cottage, just south of the Natural Bridge Hotel. Jefferson and two granddaughters visited the Natural Bridge in 1817, and Patrick Henry led them on a tour. Eighteen- year-old Cornelia, whose mother was Jefferson’s daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph, wrote that Patrick Henry worked for an hour to lay planks and logs to help them navigate the hike. His brother John V. Henry wrote to Jefferson on April 25, 1819 that Patrick was being threatened by neighboring landowners about taking his house, after “he has devoted two years laber.” It is probable that Patrick Henry visited Jefferson at Monticello that year.

A newspaper item in 1827 related a story from Patrick Henry that George Washington had once thrown a “dollar from the bottom of the chasm on the bridge, the perpendicular distance of which is 212 feet. Patrick says that none of the numerous attempts to imitate this projectile force have come nearer to its accomplishments than hitting the side of the bridge, which is of itself no ordinary feat.”

Patrick Henry became the first guide for the Natural Bridge, as reflected in an 1838 article recounting a visit there in 1818 by several Washington College students. It referred to a “sort of journal, kept to record visiter’s (sic) names by poor Patrick Henry, a man of color, who kept the bridge.”

On Jan. 10, 1829, Patrick Henry made his will, and died soon after, in his early 40s. John V. Henry and James R. Jordan were witnesses, and James Wilson, a stone mason, was named executor. He wished to be buried “at the back part of the garden attached to the house in which I now live.” He specified that “The land now in my possession conveyed to me by Thos. Jefferson if it can be retained by said conveyance I wish to be disposed of in the following manner. The family shall keep it in possession until the children arrive at years maturity after which time each shall be entitled to a third part, in case of the previous death of my wife, to be equally divided between said children Joseph and Eliza Ann.”

Jefferson did not formally convey any legal interest to Patrick Henry, but his wishes were honored for a time. The Natural Bridge and 157 acres were sold to Joel Lackland in 1835, and Louisa Henry stayed on as a servant and guide for a time. Someone later wrote of meeting an elderly Black woman who knew Jefferson.

Joseph Henry registered as a “free Negro” on May 29, 1844, age 28, 5’ 8” tall, a “high colored mulatto, short hair inclined to be straight,” born free in Rockbridge County. Nothing further about Louisa, Joseph or Eliza Ann Henry has been found. The lineage of Patrick Henry is lost to history.

Part 2 of this series will detail the lives of Williamson, Duncan, and John V. Henry.